NISA’s CEO and Head of Investment Strategies David Eichhorn participated in a panel discussion at the Treasury Market Conference held this Fall at the Federal Reserve Bank of New York. This was the 10th annual version of this conference, which was established by the Fed, Treasury, SEC and Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC) to analyze and improve the resiliency of the Treasury market in the wake of a few isolated-but-troubling episodes of impaired market functioning. We regularly attend the conference but don’t always report back to clients since the subject matter is often mired in the weeds of market structure, transaction data reporting and clearing arrangements. The plumbing of the $28 trillion Treasury market is crucial to the functioning of the global financial system, but doesn’t always provide the most exciting material for a blog post. This year was different.

The panel occurred in the context of regulators’ longstanding interest in “The Basis” trade. While there are an infinite number of basis trades in financial markets, only one deserves the honorific “The” – the basis between U.S. Treasury bonds and corresponding Treasury futures contracts. Given the size and importance of the Treasury market, perhaps that distinction is warranted. Nonetheless, we had relatively mundane expectations this year when David was asked to participate on a panel examining asset managers’ use of Treasury futures and the impact on the basis.

We were, therefore, a bit surprised when the discussion began with the acknowledgement that the proximate cause for the basis being so distorted is active managers utilizing Treasury futures for the purpose of adding levered credit beta to their portfolios. This is a widespread industry practice that we have highlighted for years. Nevertheless, we are not sure what surprised us more: the absolute scale of this substitution of beta for alpha; or the ready admission thereof. The experience highlights the importance of understanding the source of managers’ alpha and your portfolio’s true exposure to credit beta.

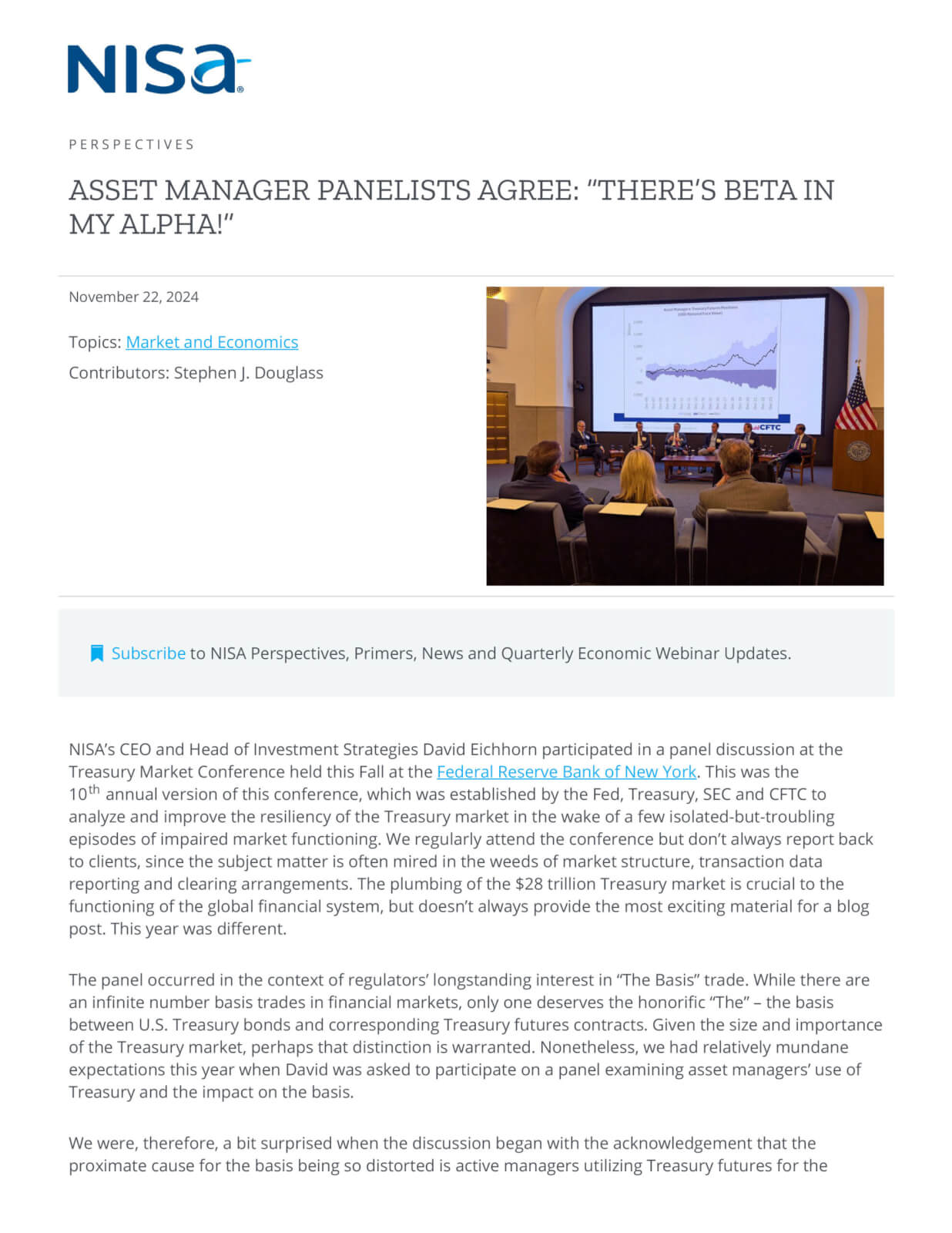

Asset Managers Have Built a Large Net Long Position in Treasury Futures

The panel moderator framed the conversation with some interesting data from the CFTC’s Commitments of Traders report, which specifies the net futures positions of different classes of investors, including asset managers, leveraged funds and dealers. Under the CFTC classification, asset managers include mutual funds and institutional investors like NISA. As you can see in the figure below, asset managers have built a very large net long position in aggregate across all Treasury futures in recent years. The figure also shows that leveraged funds, which include hedge funds and CTAs, hold an offsetting short position.

Source: CFTC Commitments of Traders Report.

The leveraged fund short position largely reflects the aforementioned basis trading, in which speculators short Treasury futures against a long position in cash Treasuries, seeking to profit from the relative value spread between the two closely-linked securities. In the Treasury market, regulators consider basis trading a double-edged sword: it promotes efficient market functioning in normal times by preventing futures prices from deviating too far from the value of the underlying security; but it increases the risk of deleveraging episodes during periods of volatility. We’ll leave that debate for another day, because the focus of the panel was on the asset manager long position.

Long Futures, to What End?

NISA clients are included among the asset manager long position shown in Figure 1 (reporting is mandatory). Most of the long futures position held by NISA clients serves the purpose of hedging the interest rate risk embedded in a pension liability – a risk-reducing exercise for those plan sponsors. It seems that many of our peers are buying Treasury futures with the explicit intention of increasing risk – specifically, credit risk. At the conference, the other panelists acknowledged that it was common practice in fixed income engagements to reduce the allocation to cash Treasuries in order to go overweight riskier credit products that offer higher yields. This strategy typically leaves the portfolio underweight duration, which is then replaced with Treasury futures. These managers are effectively using a basis trade (sell cash Treasuries and buy futures) to generate the cash to fund the levered credit beta.

This systematic demand from asset managers to own Treasury futures has caused futures to trade persistently rich to cash Treasuries in recent years. Asset manager demand has pushed the basis wider (and incentivized hedge funds to take the other side of the basis trade). The Treasury Borrowing Advisory Committee (TBAC) estimated that replicating the Bloomberg Treasury Index with futures imposed an annual cost of 45 bps on average from 2018 to 2023.[i] This means that the use of Treasury futures imposes a 45 bp headwind to the levered credit beta trade. The mechanics of the trade therefore give away as much as one-half to one-third of the spread earned from buying investment grade credit over the same time period (though a smaller proportion if buying riskier credit like high yield). This cost would not be borne by an allocator who funded a credit beta overweight with cash.

Pennies in Front of a Steamroller

Even though we have long known that the asset management industry was engaging in this systematic credit overweight, we were surprised to hear the consensus accept it so openly in a public forum. Our critique is not with the logic of the strategy. A systematic credit overweight will in fact allow a portfolio to carry a higher yield than the benchmark and therefore outperform a fixed income benchmark during the less volatile early and middle stages of the credit cycle. But this strategy will dramatically underperform the benchmark when the credit cycle comes to an end during a recession or financial instability episode. It has the classic negatively-skewed return profile, the proverbial “pennies in front of a steamroller” trade. In order for this trade to generate excess returns across the full credit cycle, the manager must see the steamroller coming and step off the road before they get flattened. The history of financial markets demonstrates that this market-timing skill is exceedingly rare.

Betting on Bailouts

This strategy has grown in popularity as recessions have grown less frequent during the Great Moderation and interventionist central bankers have acted aggressively to limit downside risk when financial instability events do occur. As one of the panelists at the conference acknowledged, the industry engages in this practice in part because they expect the Fed will bail them out in the event that the trade goes south. This is a cynical view of the bond market, but it’s not wrong. As David mentioned on the panel, the Fed has fostered this moral hazard by repeatedly stepping in to support fixed income markets during times of stress.

Play the Game the Right Way

Our criticism of the industry’s systematic credit overweight is twofold. First, it’s not alpha. It’s just levered beta. True alpha is rare and commands a premium price. Beta comes cheap these days. Allocators should not pay active management fees to obtain levered beta. Second, this practice may leave allocators exposed to hidden risks in their portfolios. If the majority of fixed income managers are systematically long beta, then they will be correlated with the benchmark and with each other – in good times and in bad. When the credit cycle comes to an end, allocators may find that their portfolios contained beta masquerading as alpha. This is exactly what the performance data show, as we have demonstrated in several prior notes:

- The excess returns of other fixed income managers are positively correlated with credit spreads, and with each other. NISA’s excess returns have historically been generally negatively correlated with credit spreads and with other managers.

- Despite the “Fed put” limiting their downside, most fixed income managers dramatically underperform their benchmarks during periods of economic and financial volatility.

- The benefits of manager diversification decline significantly if the managers are correlated with one another.

If an allocator wants to pursue a systematic credit overweight, we will urge caution but we won’t talk them out of it. We will simply encourage them to play the game the right way. First, make sure it’s a conscious choice – don’t unknowingly carry a levered beta position. Second, obtain the exposure in the most efficient manner possible. Don’t give up 45 bps of the additional carry by funding the beta overweight with the basis trade. Don’t pay active management fees for beta. The simplest method is to increase your allocation to credit, which can be achieved inexpensively in cash fixed income or derivatives markets. This approach can be further tailored with allocations to specific corners of the credit market, like high yield. Finally, balance the systematic credit overweight with alpha that is uncorrelated – or even better, negatively correlated – to beta.

The conference replay is available here. Refer to timestamp 00:17:45 for the beginning of the panel discussion that includes David Eichhorn with key points related to this article occurring at 1:10:25.

[i] See slide 80 of the TBAC presentation titled “Illustration of Futures Replication Costs” here: https://home.treasury.gov/system/files/221/CombinedChargesforArchivesQ12024.pdf.