After much public deliberation, President Trump announced Kevin Warsh as his nominee to succeed Jerome Powell and become the 17th Chairman of the Federal Reserve Board of Governors. Relative to the wide range of candidates Trump has considered for economic policy positions in the past, Warsh is a conventional choice that reduces the tail risks associated with monetary policy these days. News of his nomination was generally well received by financial markets, with a slight bear steepening in Treasury yields (likely stemming from his balance sheet views, as we’ll discuss), a modest appreciation of the dollar, and a yawn from risk assets. Senator Tillis strenuously reiterated his intention to block all Fed nominations from advancing out of the Senate Banking Committee until the DOJ investigation into Chairman Powell has been “resolved.” We anticipate that this roadblock will be cleared and Warsh will be confirmed by a comfortable margin in time to take office before the June FOMC meeting.

A Hawk in Dove’s Clothing?

Warsh is a conventional choice in part because he previously served on the Board of Governors from 2006 to 2011. That tenure, as well as his subsequent writings at the Hoover Institution and in the Wall Street Journal’s opinion pages, provide a lengthy public record of his views on monetary policy. Those views remained consistently hawkish from his tenure on the Board through 2016. During the depths of the global financial crisis in April 2009—when core PCE inflation was 0.8% y/y and the unemployment rate was 8.7%—the FOMC transcripts report him saying that “I continue to be more worried about upside risks to inflation than downside risks.” Core PCE inflation would average 1.5% over the next decade and would only top 2.0% in five out of those 120 months.

We don’t cite those figures to mock Warsh’s powers of prediction—forecasting the economy is difficult work, and we’ve made plenty of errors ourselves over the years. We recount that episode to highlight the depths of Warsh’s hawkish inflation bias. Those of us who invested through the GFC can remember: very few economists stayed that hawkish for that long after Lehman failed. This record suggests to us that his dovish pivots in 2017 and 2025 were motivated by political considerations, as he auditioned for this role on those two occasions when it became available. We don’t begrudge him for shifting his tone in pursuit of the job, but it will be consequential for fixed income investors to learn which are the chameleon’s true colors. We suspect he will continue to sound dovish early in his tenure as Chairman and may even be able to deliver an extra cut or two, relative to a hypothetical neutral baseline. But we will not be surprised if he turns out to be a hawk in dove’s clothing after a few years on the job.

Balance Sheet Hawk

One area where Warsh’s views have remained consistent is balance sheet policy. He objected to the Fed’s balance sheet expansion from the outset in 2008 and resigned in 2011 partly in protest of QE2. He has maintained those objections right up through 2025. Warsh sees QE as the source of many ills: price inflation, asset bubbles, inequality, damage to the Fed’s credibility, higher inflation expectations and—perhaps most importantly given the circumstances—fiscal profligacy. He has repeatedly argued that the Fed’s asset purchases represent debt monetization that shields fiscal policymakers from the higher interest rates that might otherwise ensue from excessive deficits. We are sympathetic to this view, and encouraged by Warsh’s consistency on this subject at a time when fiscal dominance is a rising concern.

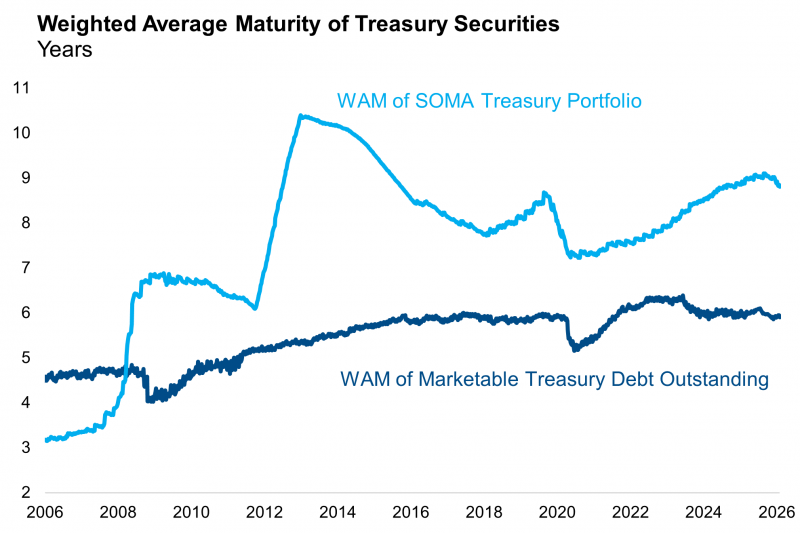

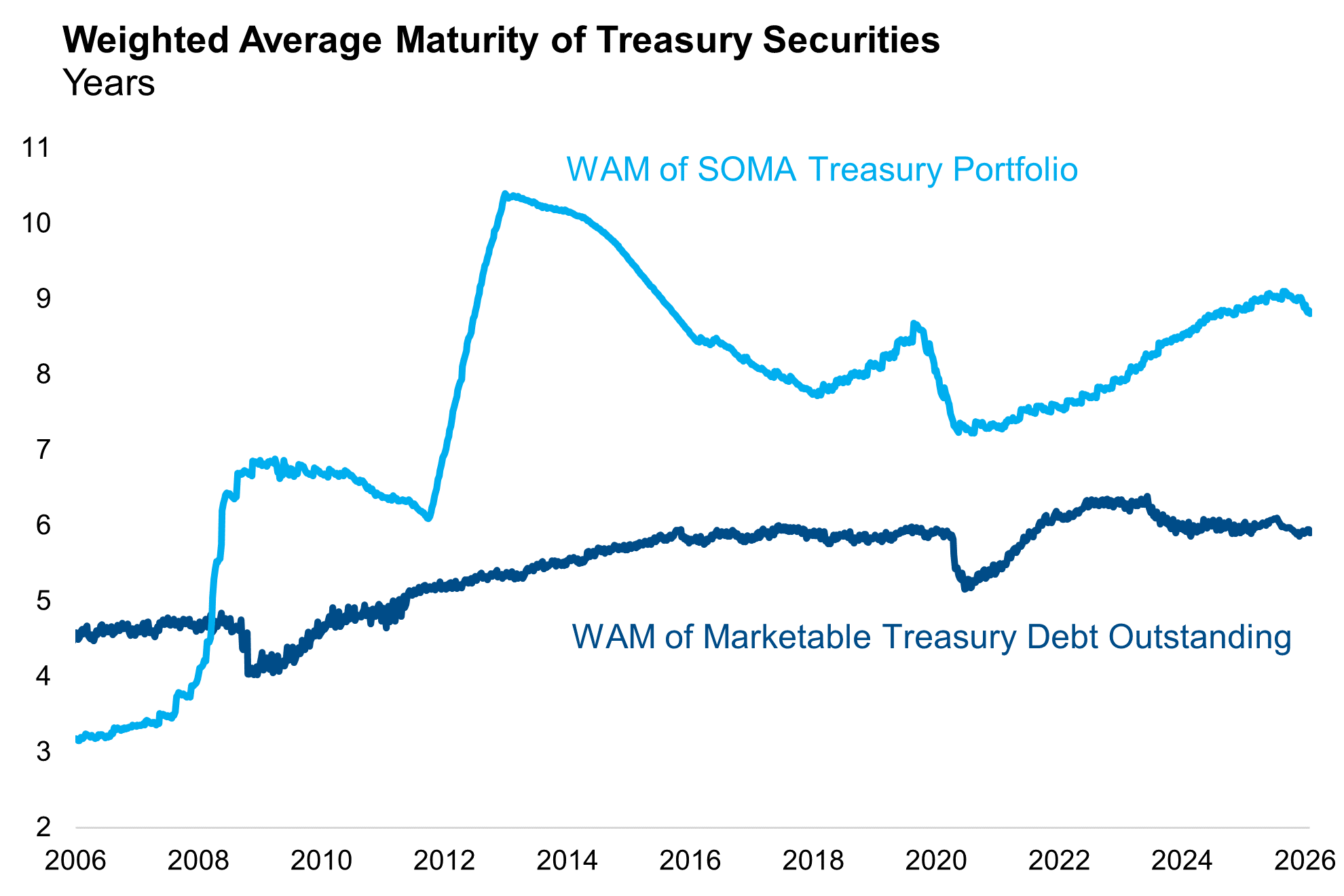

That said, Warsh’s desire for a smaller balance sheet does seem diametrically opposed to the Trump administration’s stated objectives of lower 10-year Treasury yields and tighter mortgage spreads. We suspect that tension will be resolved very gradually. The Fed has already completed the full cycle from QE to QT to reserve management purchases and will continue growing the balance sheet roughly in line with nominal GDP. The only near-term decision point on balance sheet policy is the composition of the Fed’s portfolio. The System Open Market Account (SOMA) portfolio still contains $2 trillion in mortgage securities and a Treasury portfolio with a weighted average maturity (WAM) about three years longer than the outstanding market.

Sources: Federal Reserve, Treasury Department, Bloomberg.

The Fed has already publicized their principles for balance sheet normalization, which include a desire to return to an all-Treasury portfolio and to shorten the WAM of the Treasury portfolio. A shorter SOMA WAM would translate to a higher term premium and a steeper yield curve, all else equal. That transition may proceed more quickly under Warsh than others, but we suspect the change will be incremental. It’s also worth noting that the Treasury Department is aware of the Fed’s increased demand for bills and will likely respond by raising bill issuance and shortening the WAM of outstanding Treasury debt. If Fed demand and Treasury supply are chasing each other towards a shorter WAM, the impact on yields may be marginal.

If Chairman Warsh really wanted to shrink the balance sheet by a few “trillions” as he claimed last year, he would likely have to abandon the current ample reserves framework for controlling short-term rates and return to the scarce reserves framework that prevailed prior to the GFC. That may be impossible given the increased volatility on the liability side of the Fed’s balance sheet. It would likely require significant deregulation of the banking sector to reduce reserve demand. Even if it were possible, it would take many years to build consensus within the FOMC for that transition, which is unlikely to occur prior to the next scheduled framework review in 2030.

Evolution not Revolution

Speaking of FOMC consensus, it bears repeating that this is how the Fed has operated for many decades. The Chairman counts for only one vote among the 12 votes that decide monetary policy. His or her power derives from the ability to build consensus and sway the vote when the decision is a close call. Chairman Powell deftly wielded that power in 2025 by guiding a committee divided by mild stagflation towards the dovish path of insurance cuts. Our baseline forecast for 2026 is for the labor market to stabilize and disinflation to resume in the second half of this year after tariffs have fully passed through to prices–a combination which will allow the Fed to cut rates in September and December. We do not change that view as a result of Warsh’s nomination.

Given the political circumstances of his appointment, if Warsh shows up in June arguing for an immediate cut, some of his new colleagues may wonder whether his motivations are purely economic. Warsh recently called for “regime change” at the Fed. Given the laborious task of turning the battleship that is the Fed’s balance sheet and the hesitancy he may face from the hawks on the FOMC, we suspect his early tenure at the helm will be one of incremental change rather than revolution.