The April payrolls report showed little change from the labor market dynamics of the past year. This was a relief to the minority of analysts who expected to already see the labor market impact from the trade policy shock in early April. The reference week for this report was April 7-11, so it was a close call whether we’d see much impact from the April 2 announcement. But, remember that most of the survey questions inquire about employment, payrolls, job searching, etc. over the prior 2-4 weeks. We did not expect to see much change in this report, and continue to believe that the inflationary impact from tariffs will arrive sooner than the decline in real activity and employment.

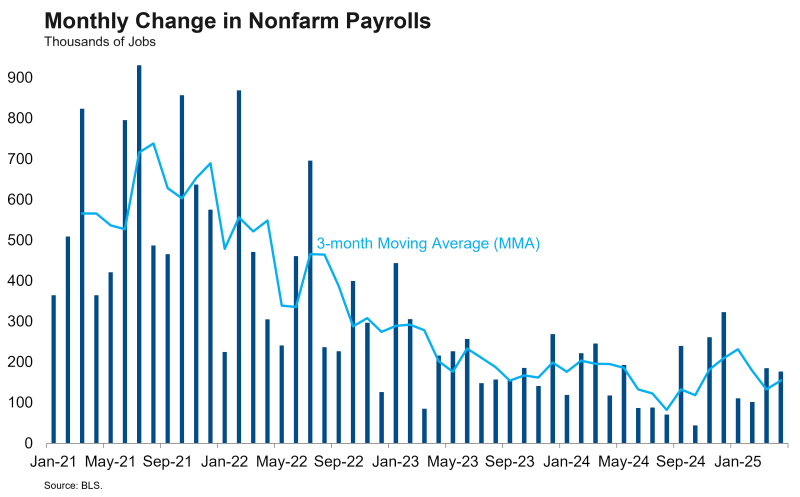

The April report reflected the status quo that we have observed since the middle of 2024. Job creation declined steadily in 2022 and 2023 but has stabilized since the middle of 2024 around a level of 150k monthly payroll growth. The labor market did its part in achieving a soft landing even if inflation victory remained just beyond the Fed’s grasp heading into President Trump’s “Liberation Day.”

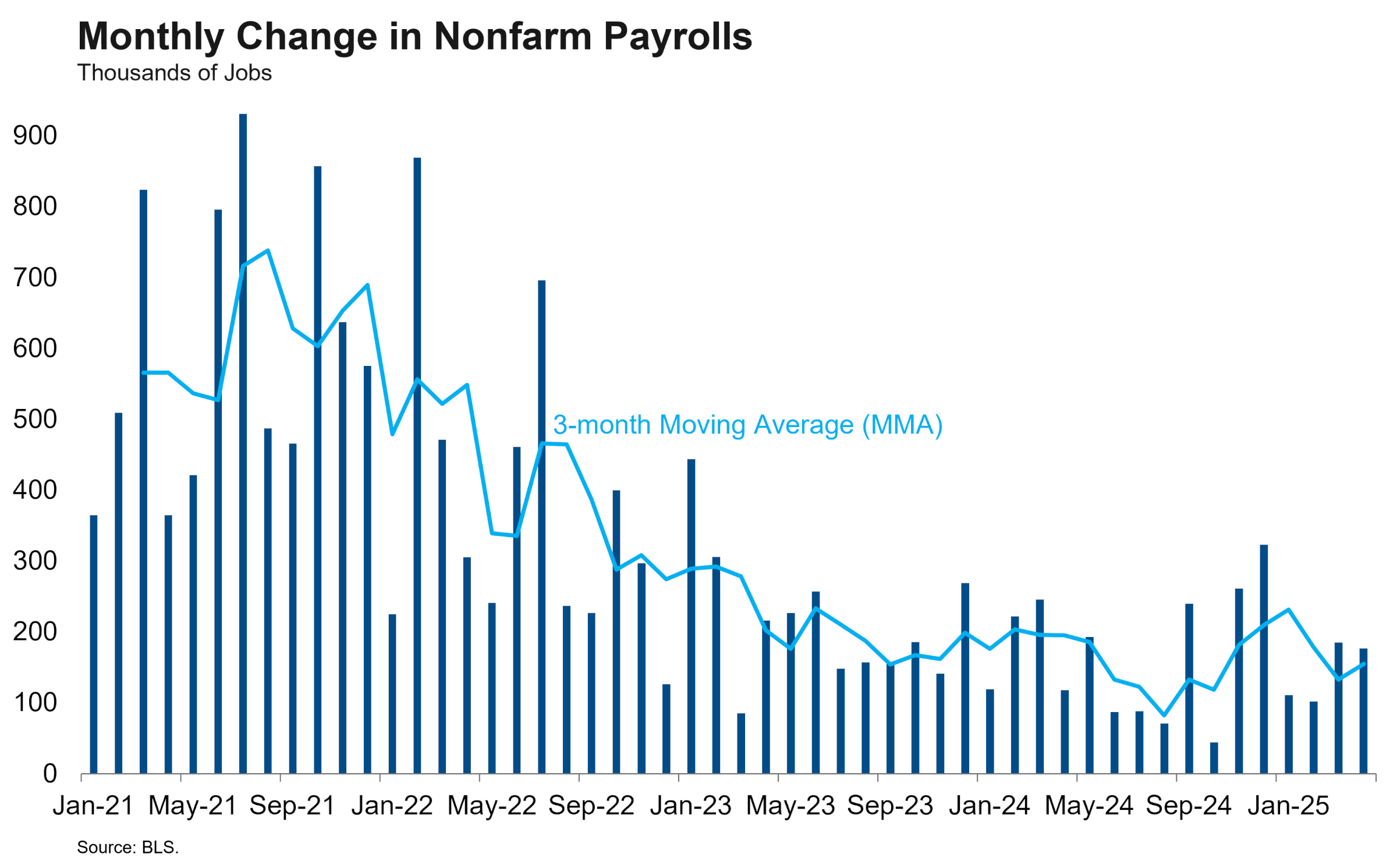

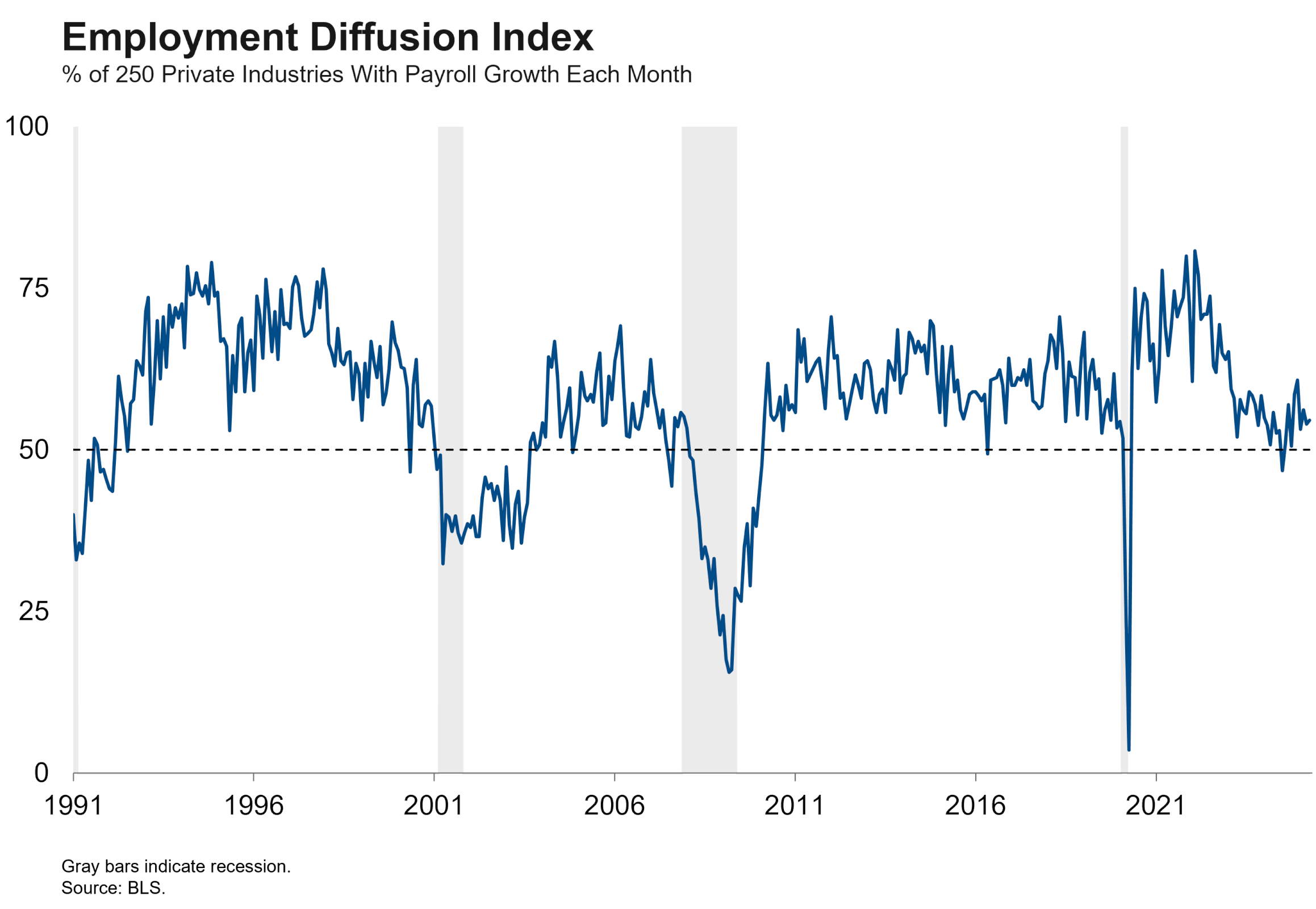

That stabilization has been welcome versus the alternative, but it does not represent a great deal of strength. Job creation has been relatively narrow across industries, as a depressed diffusion index shows. Healthcare and government alone have accounted for an abnormally large share of payroll growth in recent years.

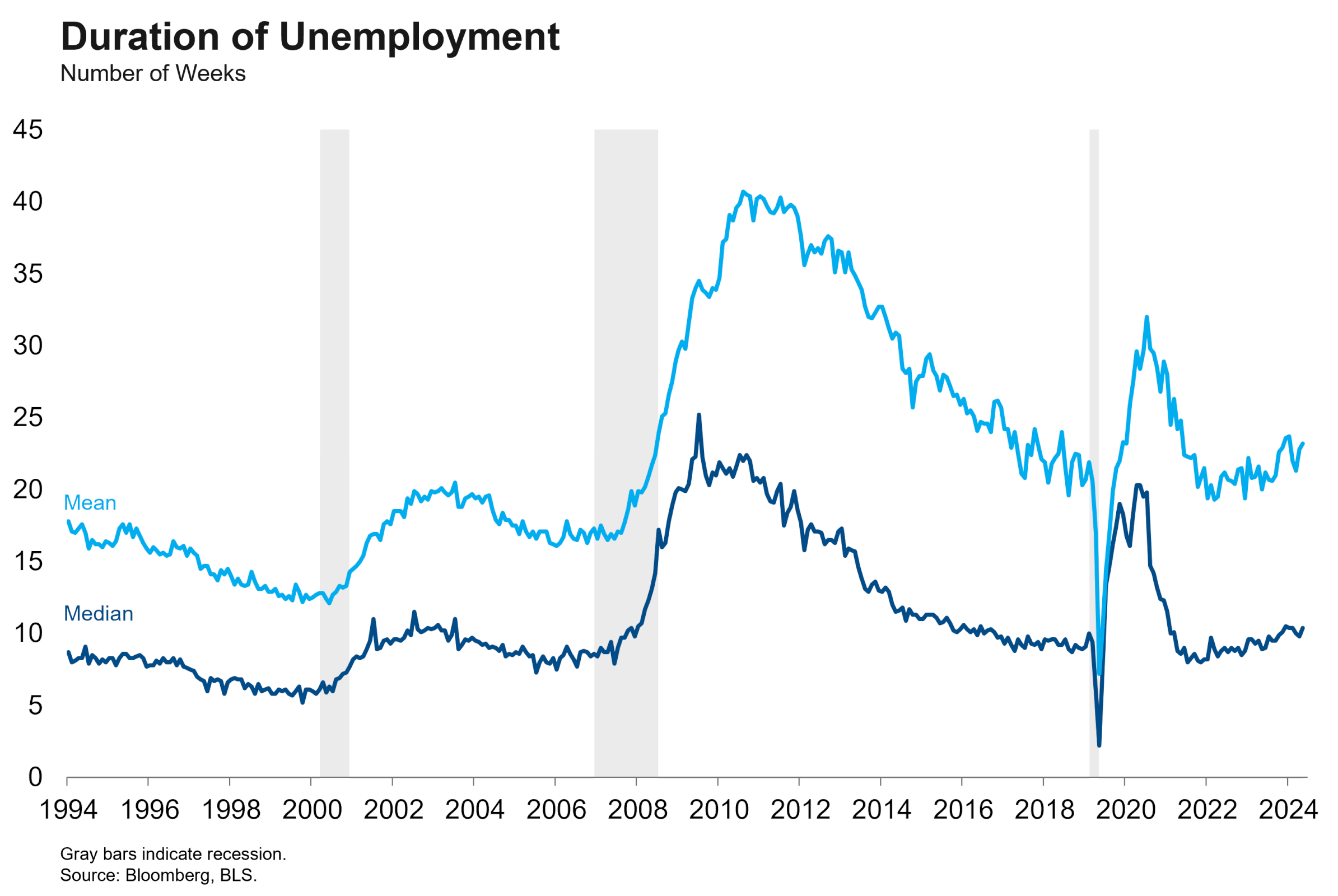

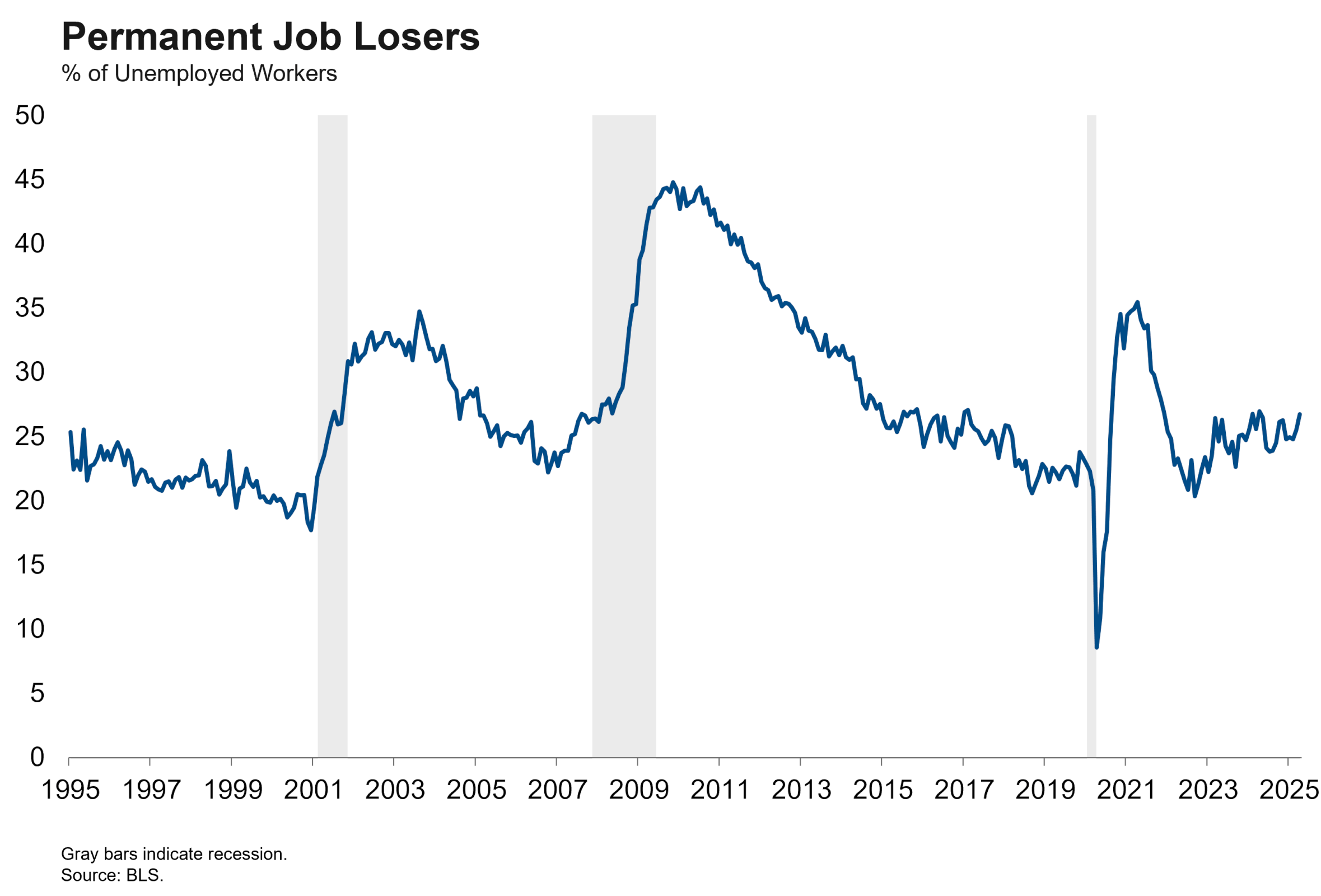

The low hiring, low firing dynamic we described in a prior note is also characteristic of a late-cycle labor market that has allowed some cracks to form. More people are getting stuck in unemployment for longer periods of time. This has caused the headline unemployment rate to rise gradually, but there are other signs below the surface. The duration of unemployment has been creeping higher. The stickiest form of unemployment, permanent job losers, has been rising not just in the absolute but also as a share of unemployed workers. It’s a good time to have a job, but a bad time to look for a job.

It’s rare to see variables like these rise gradually – their typical pattern is to grind lower during the expansion and then rise quickly when the recession arrives. Their recent gradual increase reflects an underlying feebleness to the labor market despite the headline stability. The labor market could break either way from this stable-but-vulnerable status quo. A positive shock to labor demand could certainly generate new momentum, but a negative shock could risk pushing the labor market over the tipping point into a layoff cycle. The low hiring rate is of particular concern, because it leaves little cushion for employers to reduce labor costs without resorting to layoffs.

The question now is: how much of a negative shock to labor demand have we just received? Business sentiment has clearly been damaged, but it could in theory rebound if the Trump administration continues to moderate trade policy from the extreme levels announced on April 2.