The trade deal between the U.S. and U.K. announced yesterday appears to make only minor changes to current trade policy between the two nations. Details are scant as no text has been signed, and the White House fact sheet is fewer than 750 words. Based on what we know so far, the substantive compromise of the deal is for the U.S. to reduce sectoral tariffs on automobile, steel and aluminum imports from the U.K. in exchange for the U.K. to ease tariff and quota restrictions on ethanol and hormone-free beef imports from the U.S. Most importantly, the agreement leaves in place the 10% “Liberation Day” tariff on all other imports from the U.K.

Relative to the status quo on Wednesday, this agreement therefore results in slightly lower tariffs on imports from the U.K. and the potential to increase U.S. exports of agricultural products by about 6% from last year. Relative to the status quo on January 19, however, the net effect is a massive increase in U.S. tariffs on imports from the U.K. from 1.1% in 2024 to something in the 7-9% range depending on the details. If this agreement is going to serve as a template for other trading partners, then high tariffs are here to stay.

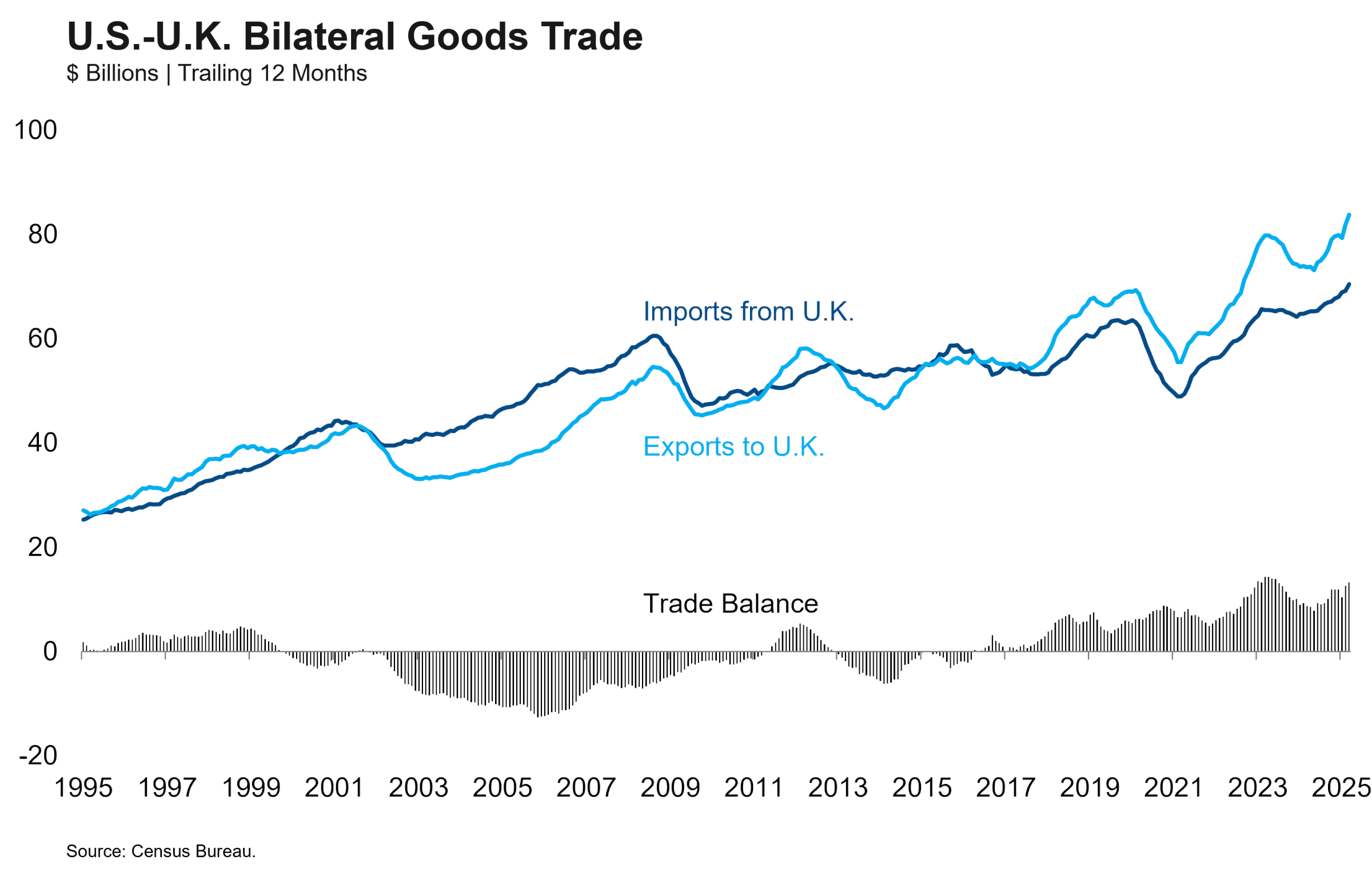

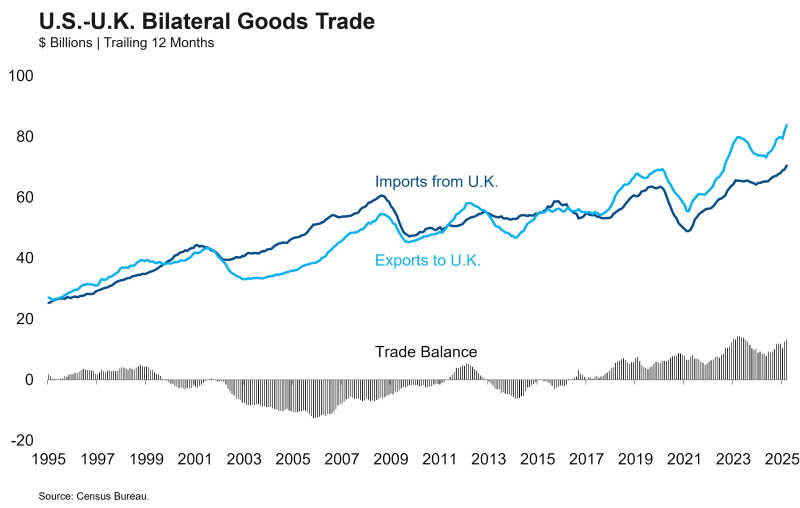

Indeed, President Trump and Secretary Lutnick both said yesterday that a 10% baseline tariff is the best that other nations can hope for as a result of their negotiations. It’s important to note here that the U.S. runs a trade surplus against the U.K. Other nations that run a surplus against the U.S. will presumably have a tougher time negotiating with this administration that views trade as a zero-sum game.

This agreement does little to change our expectations for the future course of the trade war. We expect that a universal tariff of 10% or higher will remain in place for most trading partners and that tariffs on Chinese imports will end up somewhere in the 40-60% range. Higher sectoral tariffs on autos, metals and pharmaceuticals will raise the average tariff rate while widespread exemptions will lower it. Add it all together and we appear headed for an average tariff rate somewhere around 15% with uncertainty that will last until January 2029 (President Trump casually threatened a 100% tariff on toys at yesterday’s ostensibly de-escalatory announcement).

Avoiding the stagflationary effects of this trade war requires a material reduction in tariffs. The consummation of this first trade deal does not increase our confidence that this de-escalation will occur. We leave our recession odds unchanged at 50%.