Financial markets have rebounded strongly following the de-escalation of President Trump’s trade war, mostly retracing the price declines of April. That sanguinity is understandable but may be premature. The agreements with China and the U.K. leave in place 10% universal tariffs, and those are only just beginning to impact the real economy. It’s easy to lose track of time given the frenetic pace of trade policy action this year, but Customs and Border Protection (CBP) has only been collecting revenue on the new Trump tariffs for 8 weeks.

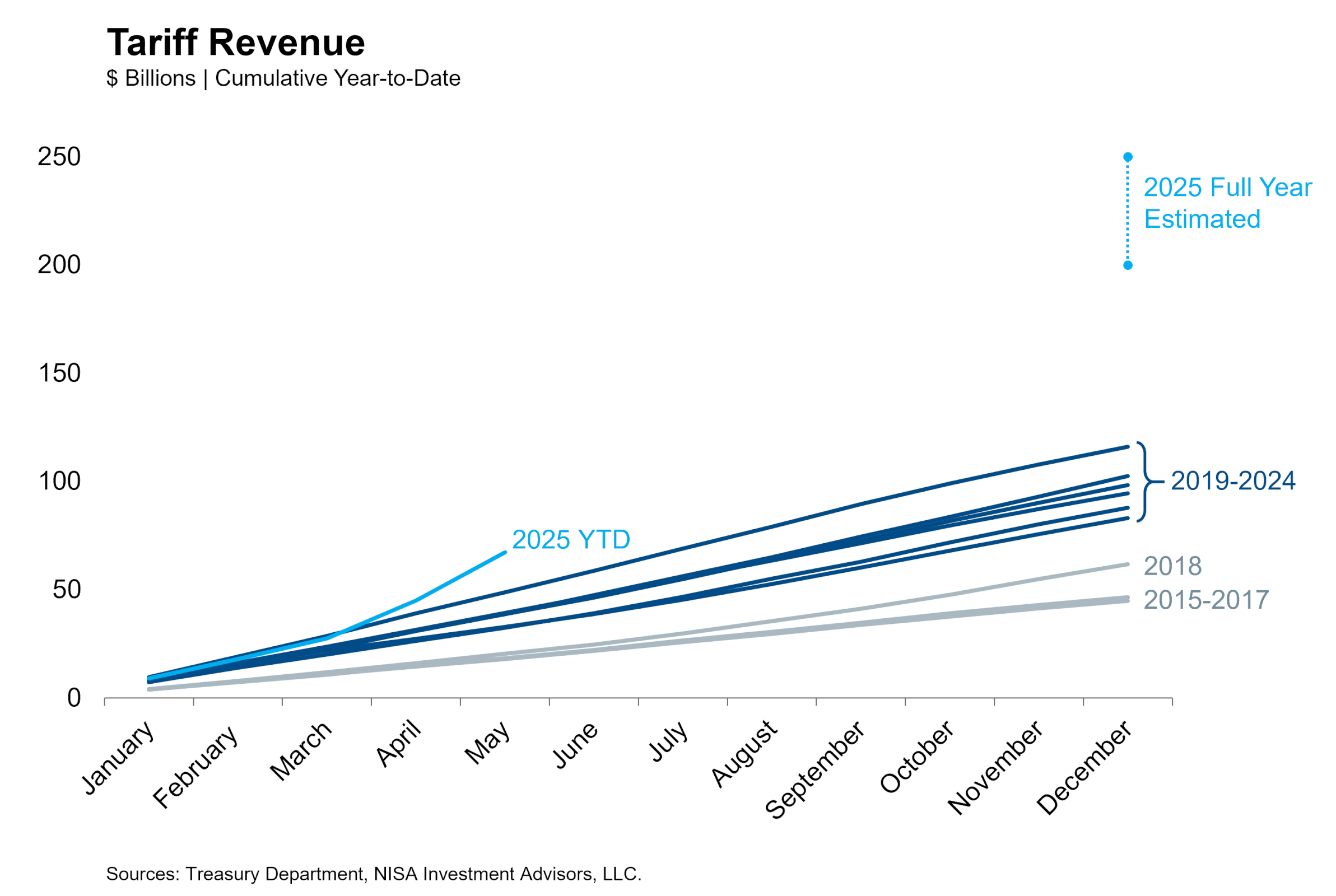

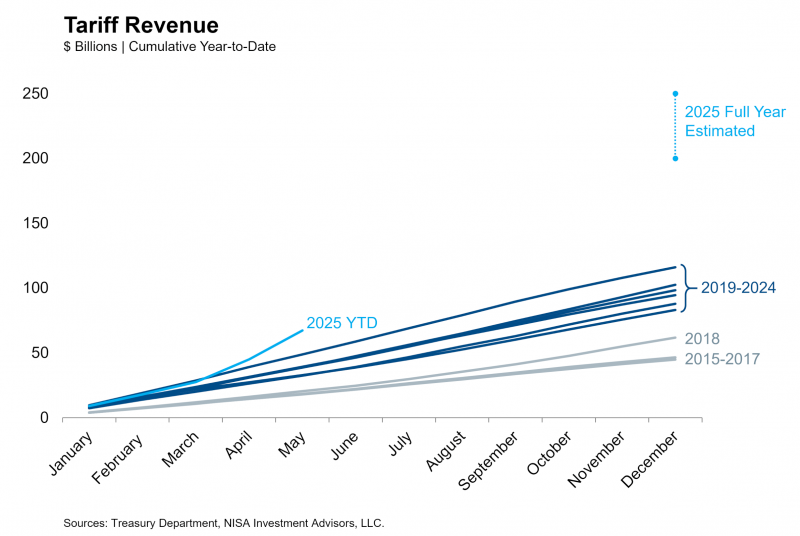

CBP has collected nearly $40 billion in those 8 weeks, which is 2.7 times the amount of revenue collected in the same period last year. That ratio is consistent with our expectation that tariff revenue will land around $200-250 billion this year versus $100 billion on average since Trump’s first trade war took full effect in 2019.

The decision by the Court of International Trade (CIT) to strike down some of President Trump’s tariffs raises judicial uncertainty that will take months to resolve, or as much as a full year if the Supreme Court takes the case. That said, we do not think these judicial outcomes will meaningfully change the trajectory of trade policy. Even if higher courts uphold the CIT opinion and deem illegal the tariffs imposed under the International Emergency Economic Powers Act (IEEPA), the president has tariff authority under a number of other statutes that are generally on firmer legal footing.

Our base case is that the IEEPA tariffs are deemed illegal, and that President Trump utilizes Section 122 tariffs, which are only allowed for 150 days, as a bridge to a wider use of Section 232 and Section 301 tariffs. These latter two tariff authorities require investigations and public comment periods, and are more targeted at specific countries or sectors (see here for a useful primer on the different authorities). These limitations are not particularly constraining. No president has ever used IEEPA authority to impose tariffs, but presidents of both parties have used 232 and 301 tariffs extensively in recent decades. We believe President Trump will be able to utilize them to achieve roughly the same 10-12% average tariff rate as we expected before his IEEPA authority came into doubt, though there could be some shifting of the distribution of tariff exposure among sectors and trading partners.

The attention of myopic financial markets may have shifted to fiscal policy, but the tariffs are just beginning to bite in the real economy. The impact will appear in the next few months in consumer prices and corporate margins as importers manage the cost increase. The president’s course correction has reduced the odds of a recession and boosted risk sentiment, but even at these lower tariff rates, this is still the largest trade policy shock in American history. The trade war may have de-escalated, but it is far from over.