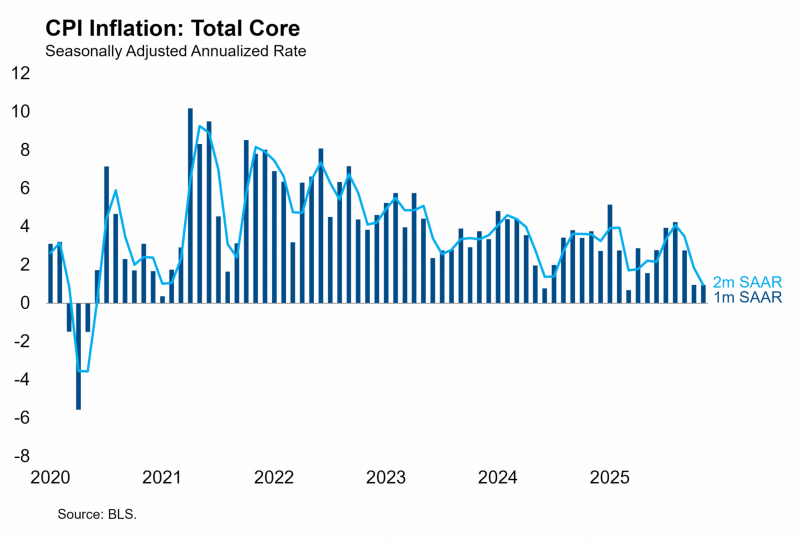

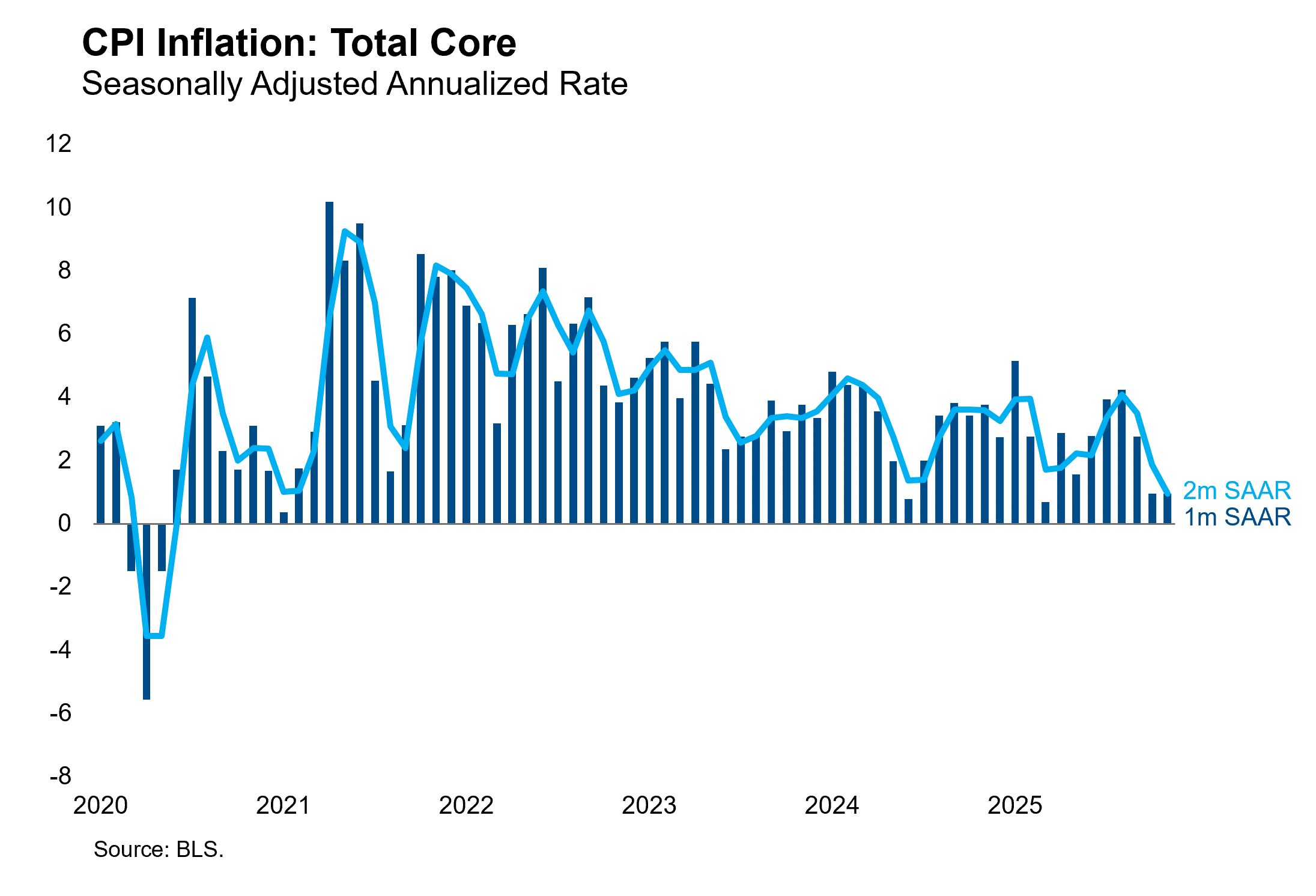

The BLS today released a heavily distorted CPI report that included some information for both October and November. The BLS stopped collecting price data when the government shutdown began on October 1 and did not resume collection until November 14. Because the data are missing, the agency did not publish October index values for most components. The data were therefore primarily presented as two-month changes between September and November. The November figures were based on price data collected during the abbreviated sampling period November 14-30. The results showed a much lower-than-expected rate of inflation. The core CPI index increased by 0.159% over that two-month period, which is the lowest two-month rate since June 2020. In the following charts, we assume the two-month change was evenly spread over October and November. This assumption smooths the monthly figures but has no impact on the two-month figures for November, which are exactly as the BLS reported.

A cycle low in the rate of core CPI inflation would be most welcome news and could clear the way for additional rate cuts in Q1, but the distortions from the shutdown introduce so much uncertainty that we expect the Fed will heavily discount this print. Fortunately, they will get a much cleaner read on the inflation picture when the December data are released on January 13 ahead of the January 27-28 FOMC meeting. We won’t bore you with all the details of the CPI imputation methods, but they probably had to resort to the most extreme “carry forward” imputation method for many components in October, which would simply assume 0% inflation for that month. The BLS did not report their imputation statistics for October, but some of the results suggest this carry forward method was used widely.

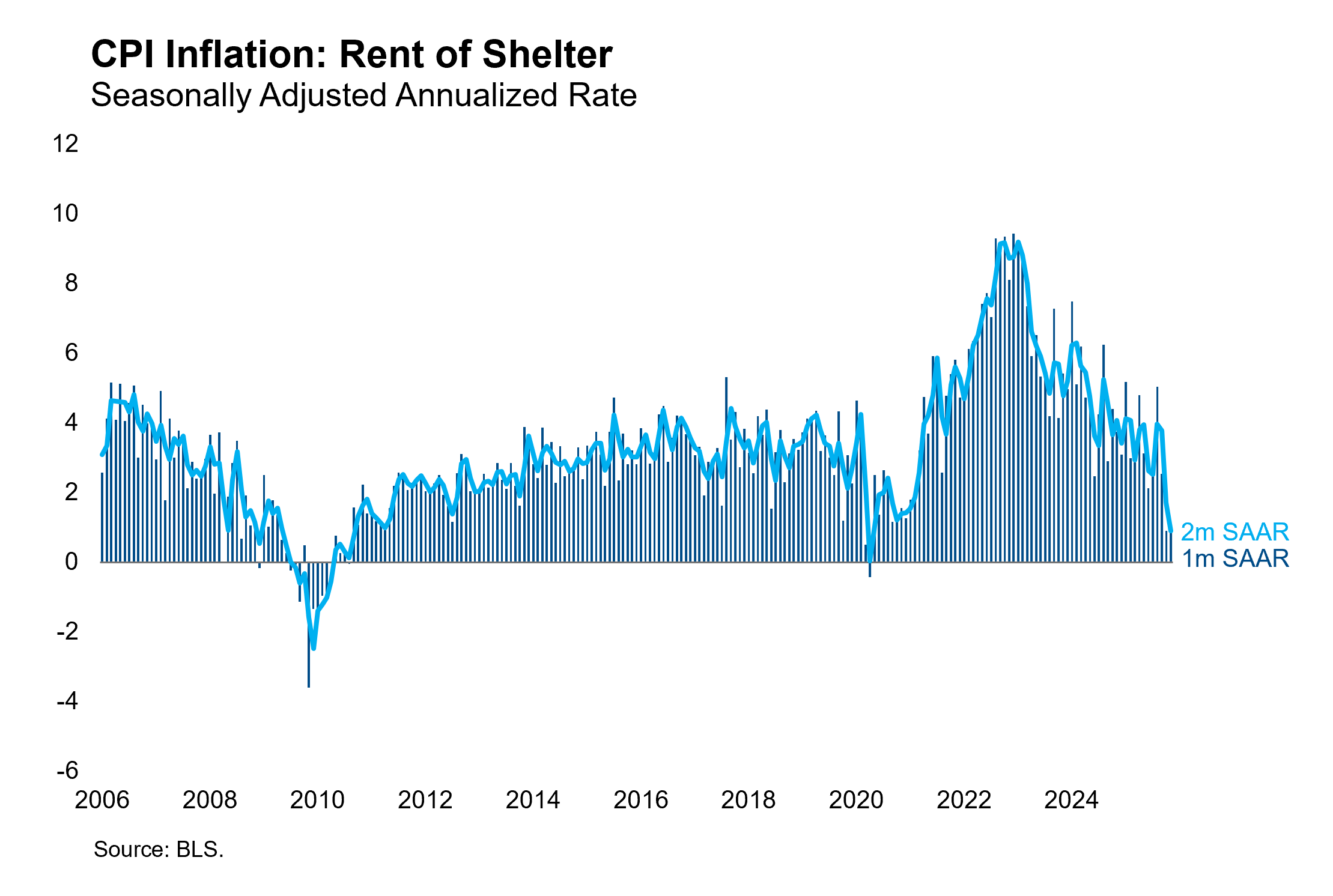

The housing component seems to be one such case. Rent of shelter (includes both apartment rent and owners’ equivalent rent) increased by 0.90% over the two months, which is the smallest two-month increase of the last two decades other than the depths of the pandemic and the global financial crisis. While we expect housing disinflation to continue, a deceleration of this magnitude strains credulity.

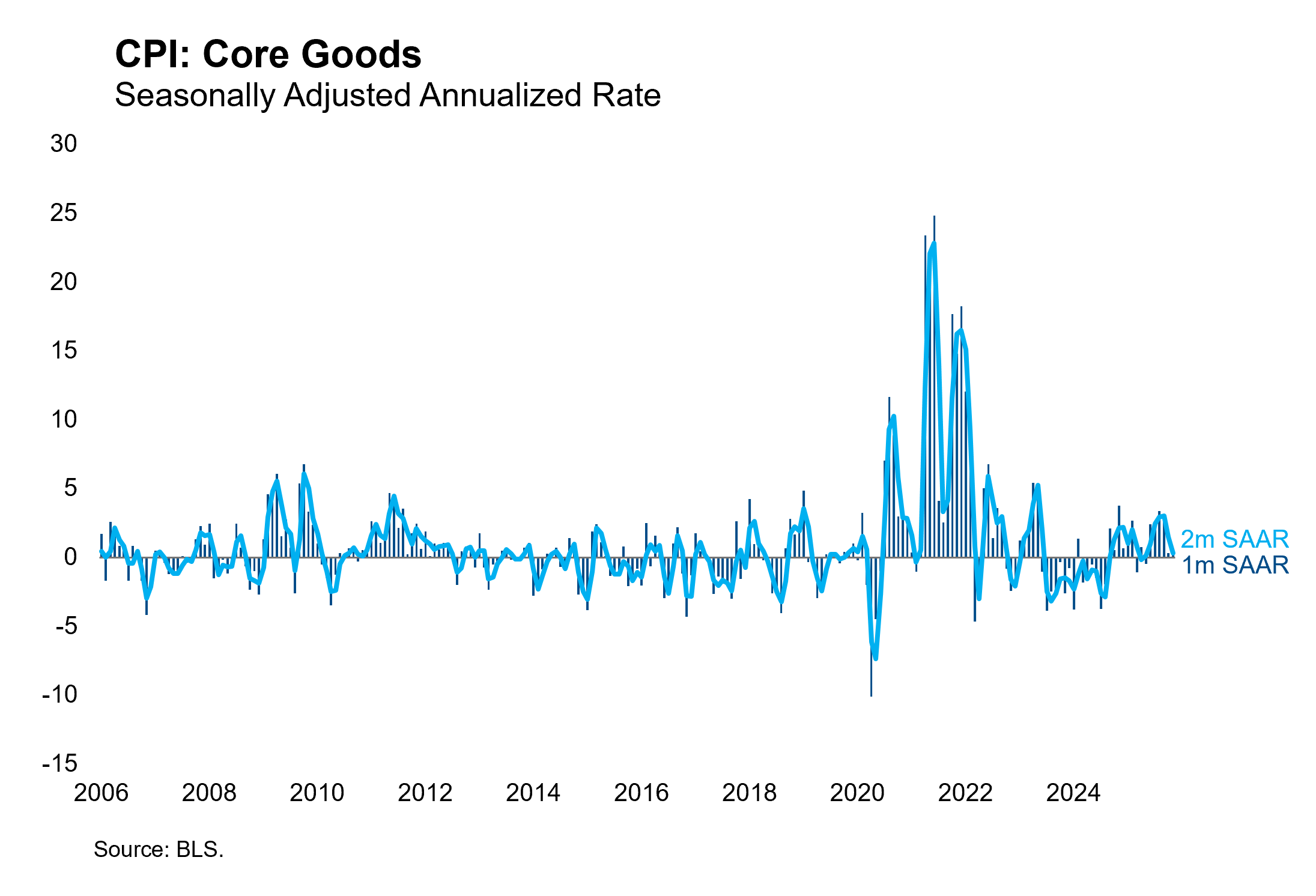

Core goods prices increased by 0.34% in the two-month period, the slowest pace since tariff implementation in May. This figure was probably biased lower because data collection only covered the second half of November when Black Friday sales were underway. The BLS usually samples prices throughout the entire month. While we broadly expect inflationary pressures to peak in early 2026 and then revert back to the soft landing path of 2024, we’ll have to wait for the cleaner December data before we update our assessment of the inflation outlook. We suspect the Fed will do the same.