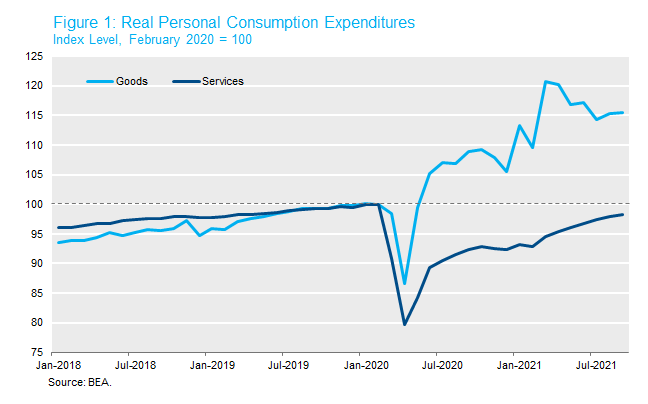

Inflation has been a popular topic in recent client conversations, with good reason. Consumer prices are rising at the fastest pace since the early 1980s, raising questions about the path of monetary policy and the low-rate underpinnings of lofty risk asset valuations. As we first discussed last year, the pandemic recession uniquely targeted the services sector. The shift in consumption from services to goods has persisted far longer than imagined at that time. As shown in Figure 1, real (i.e., inflation-adjusted) goods consumption has surged 16% above its pre-pandemic peak even as real services consumption has yet to fully recover 18 months into the pandemic. American consumers spend about $5 trillion in nominal dollars each year on manufactured goods, which are often produced and distributed along the most complex globalized supply chains in the economy. It should be no surprise that shocking this sector by 16% in real terms in the middle of a pandemic has caused severe disruption.

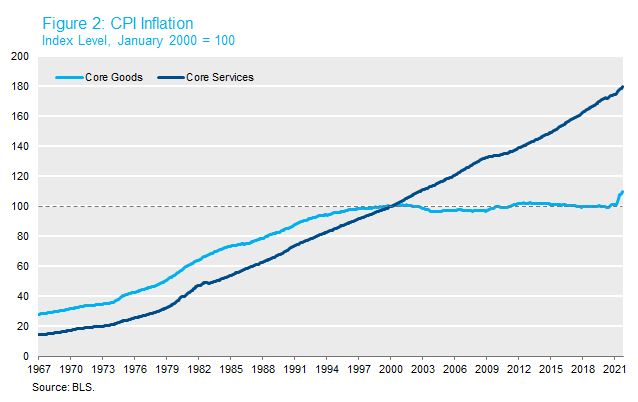

Goods supply has proven too inflexible to keep pace with this demand shock, causing a surge in goods prices that accounts for effectively all of the core inflation surprise in 2021. To demonstrate how unusual this phenomenon is relative to recent history, Figure 2 shows prices for goods and services excluding food and energy in level terms rather than rates of change. For most of the postwar period, goods and services prices rose at a roughly similar pace. When China’s low-cost manufacturing powerhouse joined the global trade economy at the turn of the millennium, goods prices abruptly stopped rising. According to these CPI measures, core goods prices were exactly flat between January 2000 and February 2020. Since then, core goods prices have risen by 9.8%. This is indeed an alarming rate of inflation for an 18-month period. But it is also accurate to say that goods prices are higher by 9.8% over the past twenty years, which is not so troubling in contrast to the 80% increase in core services prices during the same period.

Goods supply has proven too inflexible to keep pace with this demand shock, causing a surge in goods prices that accounts for effectively all of the core inflation surprise in 2021. To demonstrate how unusual this phenomenon is relative to recent history, Figure 2 shows prices for goods and services excluding food and energy in level terms rather than rates of change. For most of the postwar period, goods and services prices rose at a roughly similar pace. When China’s low-cost manufacturing powerhouse joined the global trade economy at the turn of the millennium, goods prices abruptly stopped rising. According to these CPI measures, core goods prices were exactly flat between January 2000 and February 2020. Since then, core goods prices have risen by 9.8%. This is indeed an alarming rate of inflation for an 18-month period. But it is also accurate to say that goods prices are higher by 9.8% over the past twenty years, which is not so troubling in contrast to the 80% increase in core services prices during the same period.

The question is whether this pattern is sustainable. Will goods prices keep rising at 10% every 18 months indefinitely? That seems hard to believe. Our view is that goods prices are more likely to stabilize or even decline outright as supply bottlenecks eventually clear and consumers resume spending on leisure services. In that case, services prices will become much more important for informing the inflation debate. We are paying particular attention to shelter, which accounts for 55% of core services CPI. Services inflation could become a problem at some point in the future, but so far during the recovery it is running at roughly the same pace of the past decade. Hopefully, next year we’ll spend more time analyzing apartment rents and ticket prices and less time reading about clogged ports and trucker shortages.

The question is whether this pattern is sustainable. Will goods prices keep rising at 10% every 18 months indefinitely? That seems hard to believe. Our view is that goods prices are more likely to stabilize or even decline outright as supply bottlenecks eventually clear and consumers resume spending on leisure services. In that case, services prices will become much more important for informing the inflation debate. We are paying particular attention to shelter, which accounts for 55% of core services CPI. Services inflation could become a problem at some point in the future, but so far during the recovery it is running at roughly the same pace of the past decade. Hopefully, next year we’ll spend more time analyzing apartment rents and ticket prices and less time reading about clogged ports and trucker shortages.