The November employment situation report revealed a labor market that remains stuck in a low-hiring, low-firing morass – neither rebounding strongly nor rolling over into a recession. The report included mixed signals and was distorted by shutdown effects as we feared. This new information will do little to resolve the Federal Reserve’s debate about whether to proceed with further rate cuts. Chair Powell told us last week that the default option is to leave rates unchanged in January. We continue to believe the Fed will remain on hold through the summer or until the economy definitively breaks out of its current state of mild stagflation.

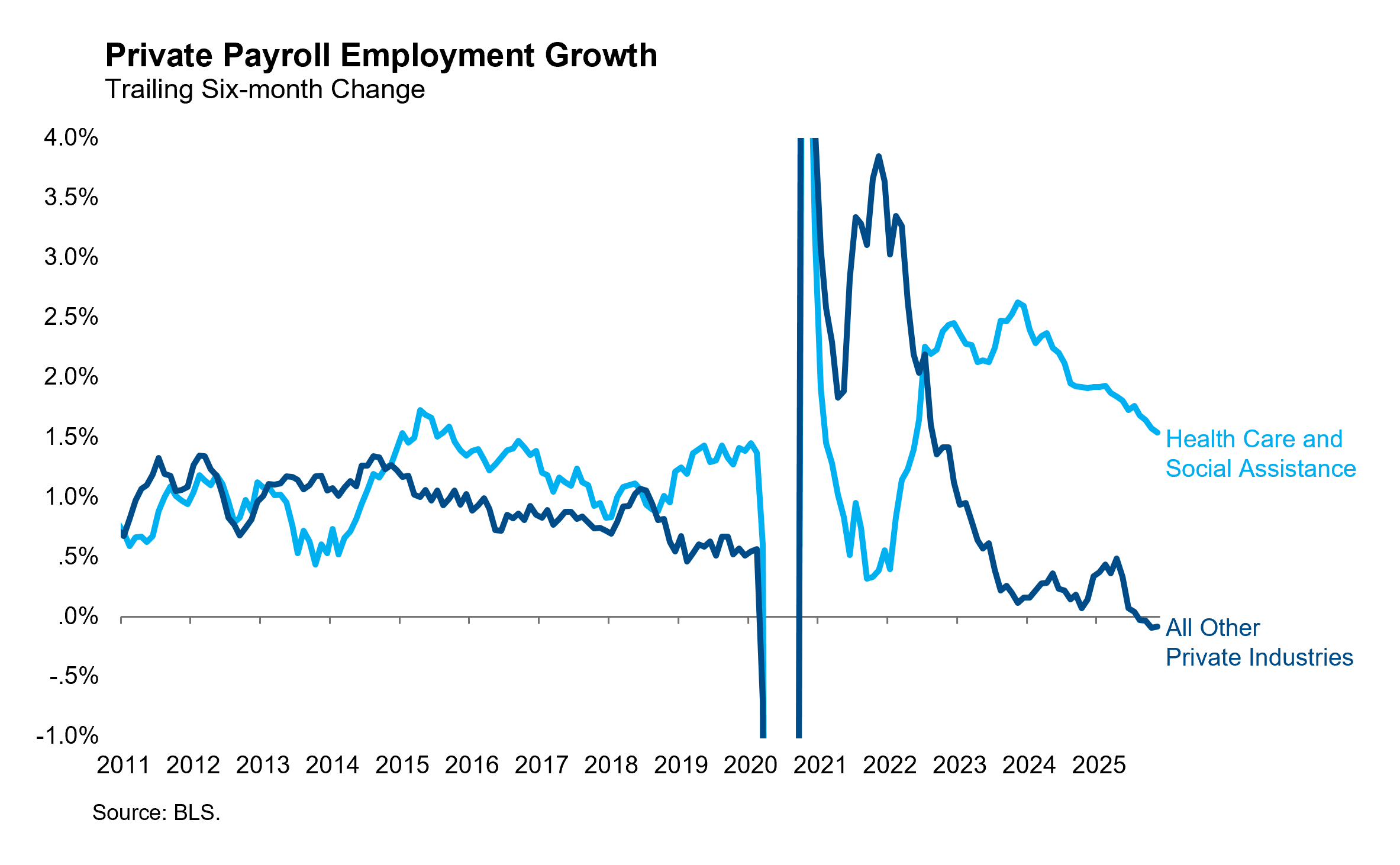

The establishment survey contained data for both October and November. As expected, the DOGE deferred resignation program reduced federal employment by 168,000 workers during the two months. Private payrolls increased by 121,000 in the same period. This brings the three-month moving average of private payroll growth up to 75,000 and suggests the trough in private job creation occurred last summer soon after trade policy uncertainty peaked. Private payroll growth appears to have stabilized, albeit at a level below what would be suggested by an economy growing above trend. The private job creation engine remains extremely narrow, with all private payroll growth in the last six months coming from the health care and social assistance industry. Yet another sign that the U.S. economy, much like the federal budget, is increasingly oriented towards caring for the boomer generation.

The household survey was not conducted in October, so today’s report only reported these results for November. The most impactful component of this survey was the unemployment rate, which rose from 4.44% in September to 4.56% in November. Because this increase was more of a result from an increase in the labor force than an increase in the number of unemployed workers, it is not a particularly troubling sign. But the fact remains: labor demand remains so weak that it cannot even create enough jobs to keep up with labor supply that is constrained by immigration policy. The result is a continued gradual increase in slack, as observed in the unemployment rate which is now above the longer-run estimate of all 19 FOMC participants.

Not only did the report send mixed messages, but the accuracy of the report itself was reduced by disruptions to the data collection process resulting from the shutdown. The BLS noted that the household survey results were subject to “slightly higher than usual standard errors” due to the unusual circumstances of the shutdown ending in the middle of the original survey reference week, and that “it was not possible to precisely quantify the total impact” of the shutdown on the establishment survey. The good news is that the Fed will get a cleaner read on the labor market with the December report, which will be released in early January ahead of the next FOMC meeting. Until that time, we expect Fed speakers will signal a cautious approach to further policy easing.