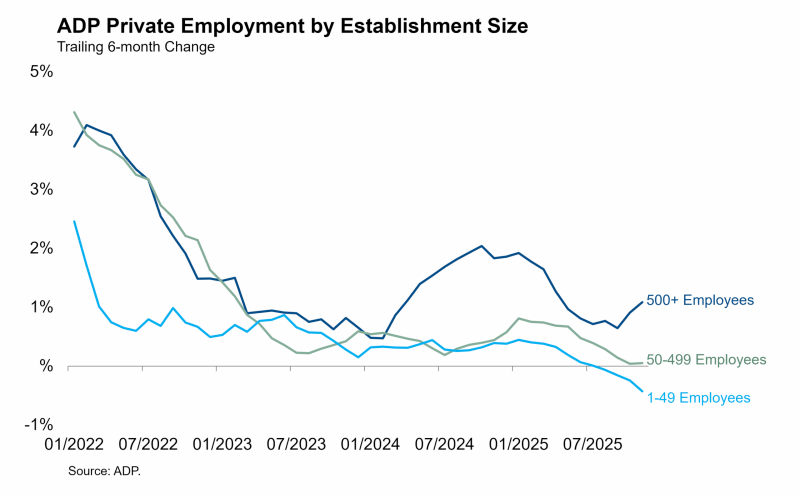

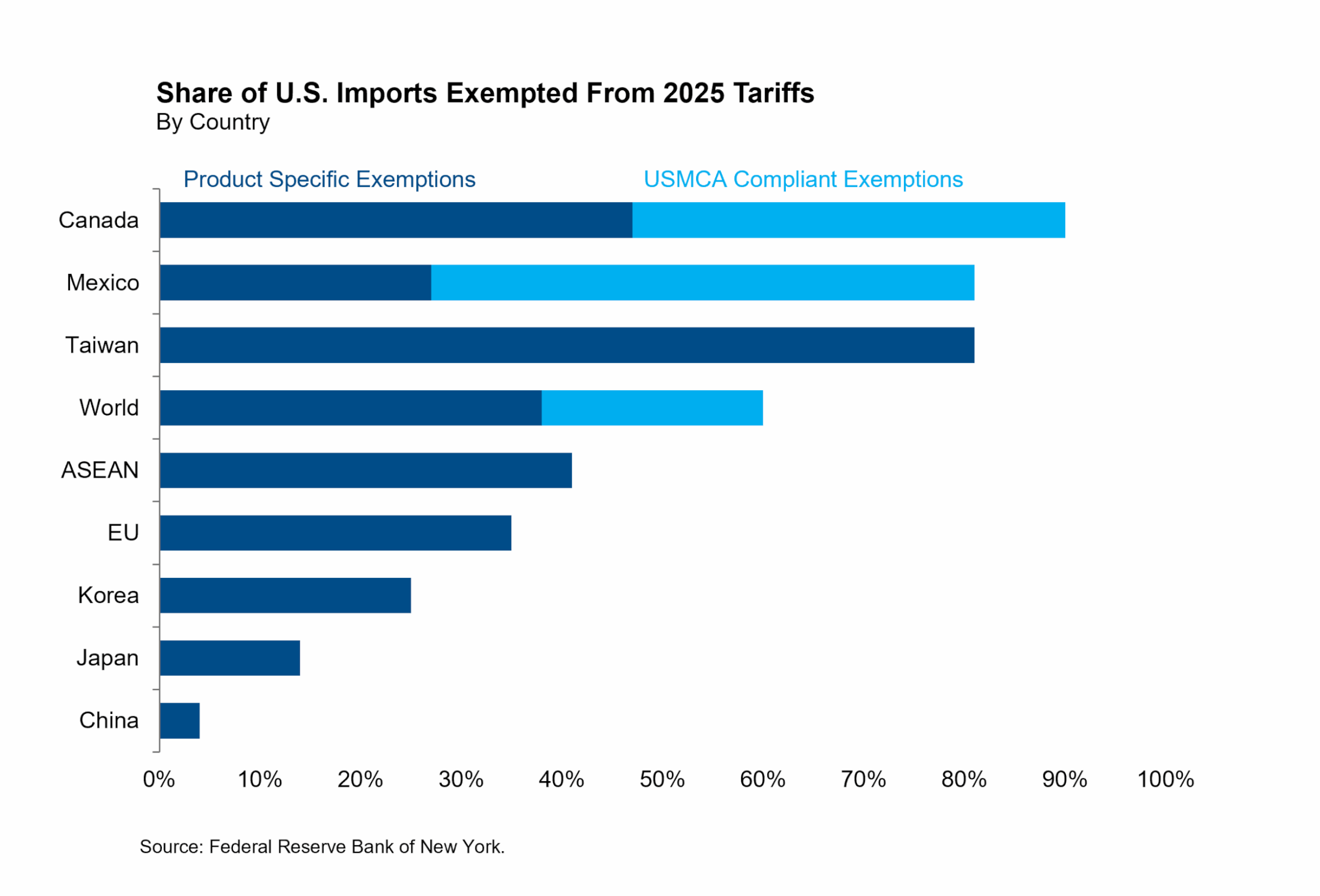

As we await the delayed BLS payrolls data, ADP estimated that private sector employment declined by 32,000 in November. This is the fourth monthly decline in the last six for this series, consistent with the stagnant nature of the labor market reflected in the official statistics this year. Because ADP tracks actual payroll data from individual companies, it can provide employment details by firm size that the BLS only provides with a lag. These ADP data show that all net job creation in the past six months came from large firms with 500 or more employees. Those firms created 267,000 jobs in the last six months, while firms with fewer than 500 employees eliminated 226,000 jobs. The smallest companies, with fewer than 50 employees, are shedding jobs at the fastest rate since 2020.

These data are concerning for those tracking a K-shaped dynamic in the corporate economy that mirrors the K-shaped dynamic in the consumer economy. Smaller, riskier and more highly levered companies have been buffeted in recent years by headwinds from interest rates and tariffs, even as large-cap tech firms soar to dizzying heights of profitability and valuation. Monetary policy transmission is faster for small firms that are more reliant on floating-rate debt (historically bank loans but increasingly private credit) as opposed to large firms that can borrow in the fixed-rate corporate bond market.[1] The distinction is even greater for large-cap tech firms, which have historically carried less debt than their industrial peers until the very recent surge in borrowing to fund the AI infrastructure buildout.

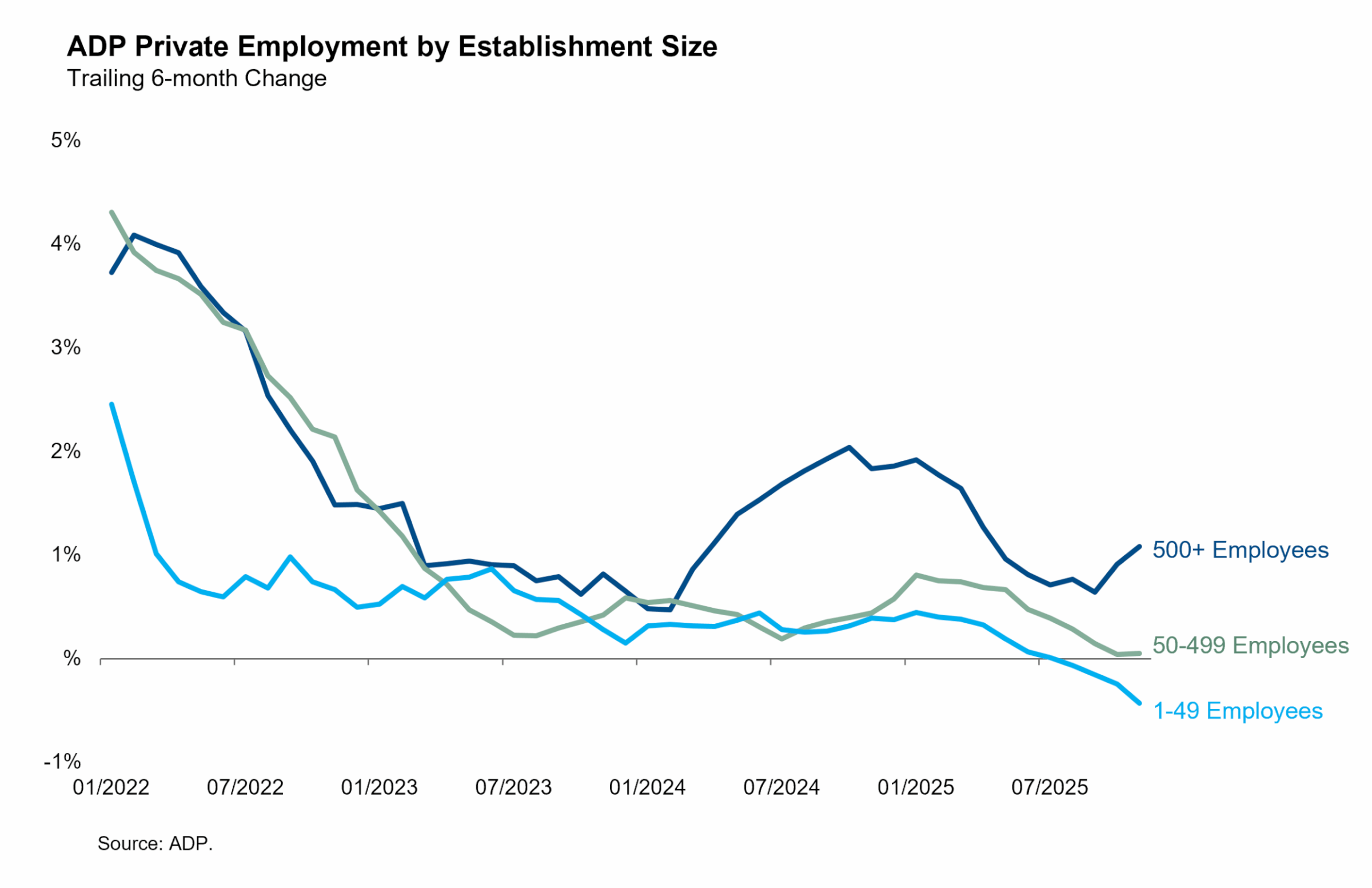

This bifurcation was especially relevant following the historic monetary tightening that began in 2022 because large firms prudently locked in low interest rates by issuing at longer maturities during the easy money years of 2020 and 2021.[2] The weighted average maturity of the Bloomberg Corporate Index increased by one full year between the end of 2019 and the end of 2021, to reach its highest level since 1998. Smaller, riskier and more highly levered firms felt the full brunt of the monetary tightening. 150 bps of rate cuts by the Fed since September 2024 have provided some relief to floating-rate borrowers, but not much. Default rates on floating rate leveraged loans have risen to recessionary levels, in contrast to fixed-rate, high yield bonds. Among the private credit universe rated by S&P, the share of borrowers with negative free operating cash flow has risen from 25% in 2021 to a shocking 43% in 2025.[3]

This two-speed monetary transmission is analogous to the K-shaped dynamic in the consumer economy where (disproportionately high income) homeowners were able to lock in low mortgage rates during 2020-2021 and insulate themselves from the tightening cycle, in contrast to (disproportionately low income) renters and first-time homebuyers whose budgets are now stretched by the highest housing costs in decades.

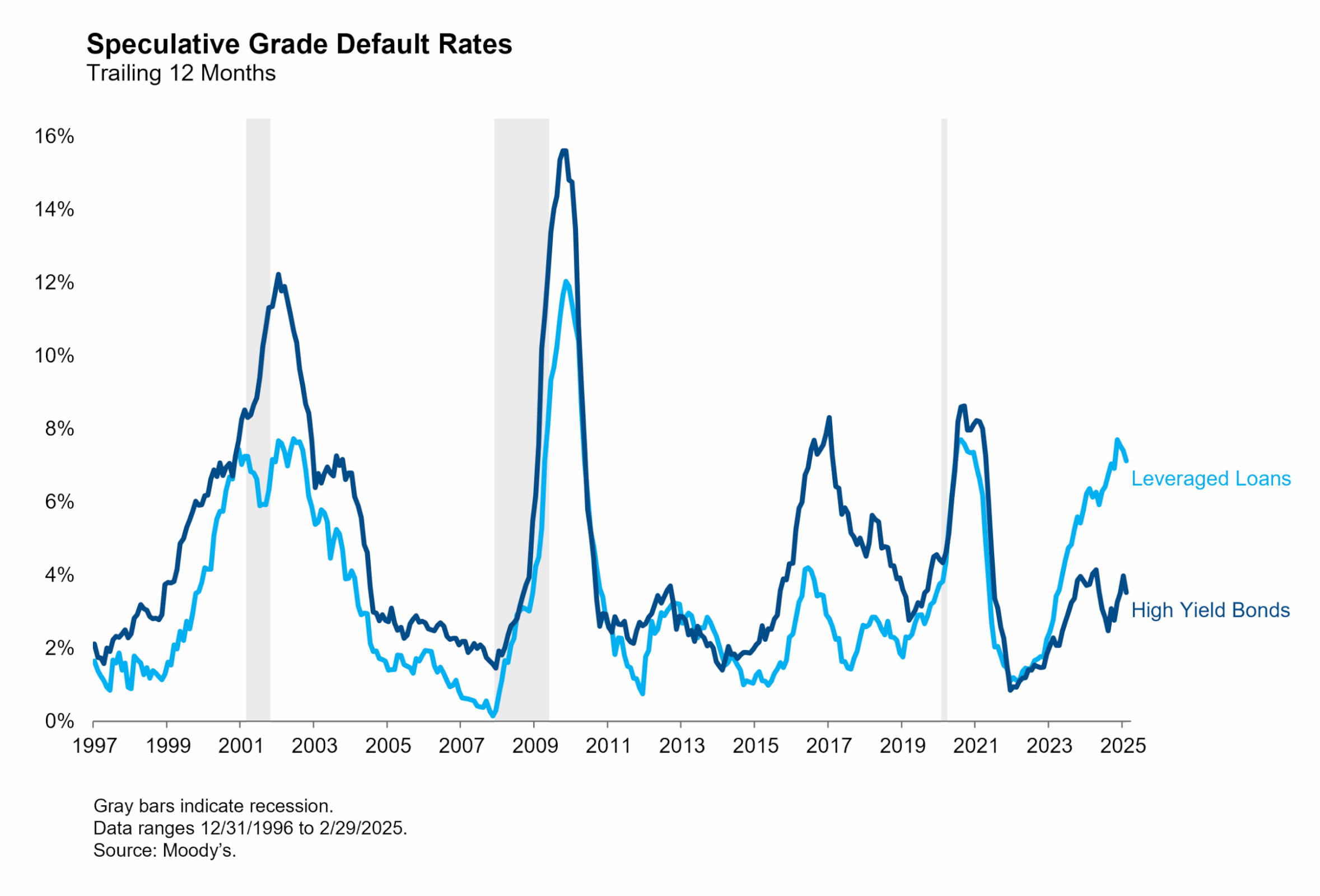

Even as rate cuts have eased financial conditions, tariffs have injected a new dose of cost inflation for goods importers. Small companies with supply chains that stretch across borders have less operational and financial flexibility to respond to the dramatic changes in trade policy. Software and media companies, like other services companies, are naturally less exposed to tariffs on imported goods. The large-cap tech firms engaged in a hardware business have lobbied for exemptions. Apple iPhones, Nvidia chips—and indeed most of the electronics imported from Asia to be installed in data centers—have been granted exemptions. Smaller companies are less likely to participate in the current lobbying surge and announce multibillion-dollar capex plans in Oval Office meetings.[4]

K-shaped dynamics in the corporate and consumer economies are a source of downside risk, but we think they are more likely to be a drag on growth rather than the catalyst for a recession. High-income consumers and large companies have shown remarkable resilience and driven the economy forward despite headwinds from monetary and trade policy. We expect that will continue into 2026, in part because those headwinds are fading as the Fed lowers interest rates and the scope of tariffs is reduced through the exemption process. But we’ll keep an eye on riskier firms and low-income consumers to consider how much their struggles might restrain job creation and growth in the broader economy.

[1] “Interest Rate Risk Exposures of Non-financial Corporates and Households” CGFS Paper No. 70, Committee on the Global Financial System, BIS, November 2024.

[2] “Non-financial Corporates’ Balance Sheets and Monetary Policy Tightening,” Miguel Ampudia, Egemen Eren and Marco Jacopo Lombardi, BIS Quarterly Review, September 18, 2023.

[3]“Private Credit And Middle-Market CLO Quarterly: A Tale of Two Markets (Q4 2025),” S&P Global, October 16, 2025.

[4]“A Gunmaker’s Lobbying Shows How Trump’s Tariffs Changed the Game,” Bloomberg, December 4, 2025.