The U.S. and China agreed last week to substantially reduce their bilateral tariffs as they continue negotiations towards a comprehensive trade agreement. New tariffs on China under the Trump administration are lowered from 145% to 30%. While some de-escalation was baked into our economic forecast, this development arrived sooner and went further than we imagined. We now expect a 10% universal tariff on all trading partners and a 10-25% tariff on China. In addition, we expect higher sectoral tariffs on autos, metals, and pharmaceuticals as well as thousands of product exclusions that reduce the scope of the tariffs. Put it all together, and we now expect an average tariff rate in the 10-12% range.

Most importantly for the near-term economic outlook, this de-escalation reduces the risk of a sudden decoupling between the world’s two largest economies. It now appears that President Trump never intended to force that decoupling, and arrived at the embargo-like triple digit tariffs rather inadvertently via tit-for-tat retaliation after “Liberation Day.” Faced with the risk of a sudden stop in Pacific trade, the administration chose instead to de-escalate without requiring any concessions from the Chinese beyond matching the tariff reduction. This catalyst is especially surprising since President Trump himself just the prior week welcomed the decline in container ship traffic at west coast ports. This episode, like the U.K. deal announced last week, provides further confirmation that the administration’s hawkish rhetoric on trade is not a reliable predictor of actual policy outcomes.

While a 10-12% average tariff rate is lower than the 15% we estimated after the U.K. deal, it would still be the highest since the Smoot-Hawley era, and higher than we expected at the start of the year. We think the enthusiasm with which risk asset markets greeted the news is partly explained by perceptions of the administration’s flexibility on trade policy. The Trump Put was exercised over the weekend, and we believe it will remain close to the money even if the average tariff rate approaches our new baseline. In other words, we expect tariffs will be reduced further below our 10-12% baseline if new pressure is applied from financial markets, the real economy, or political considerations.

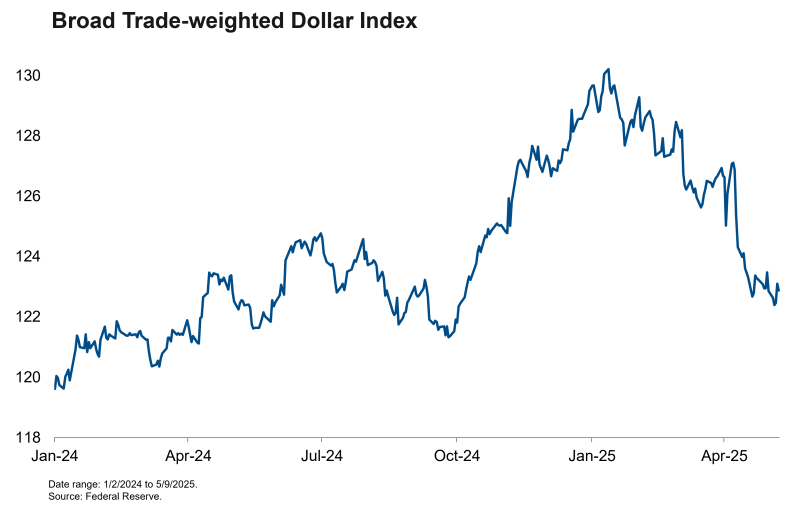

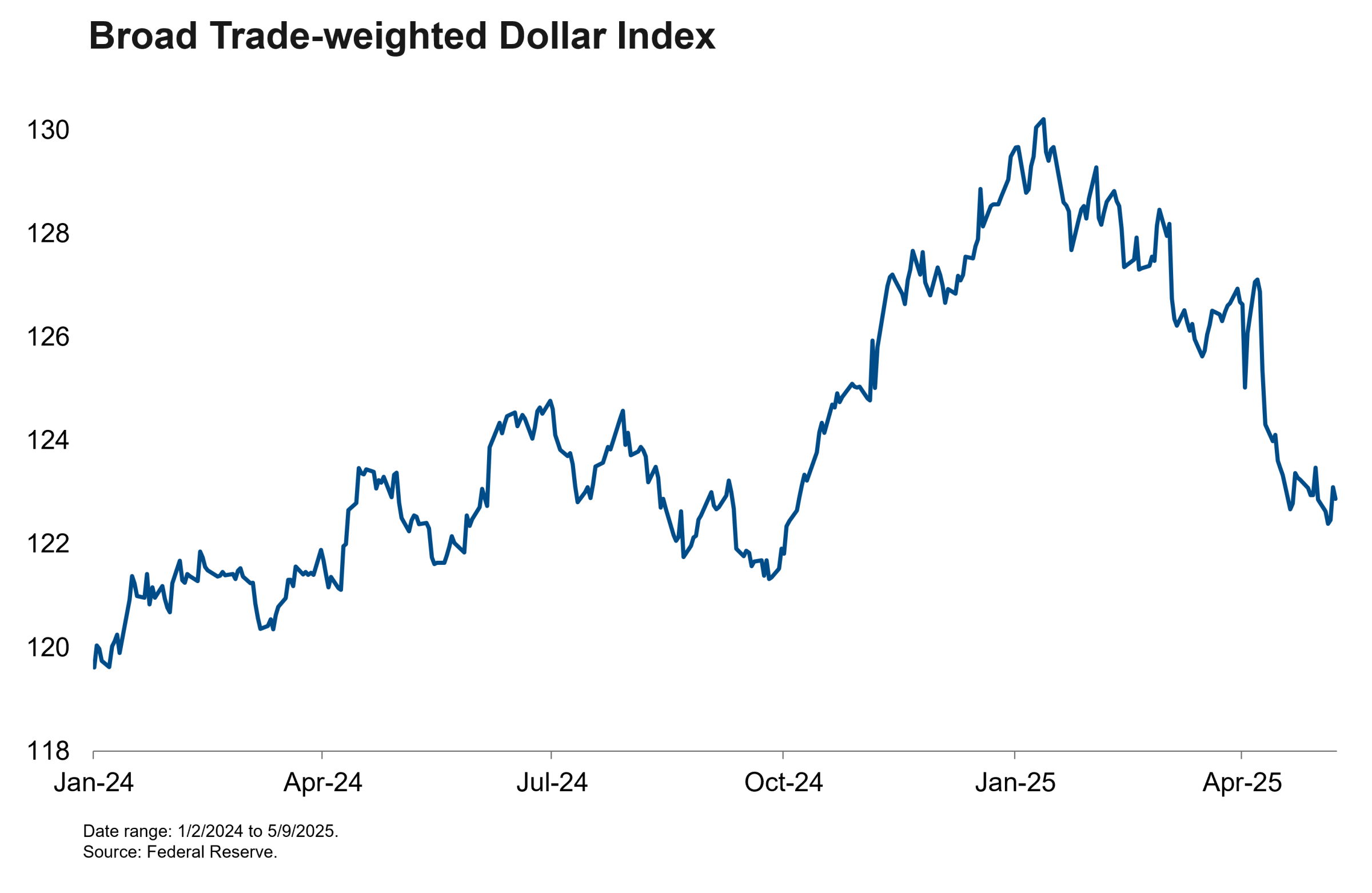

By reducing the risk of a sudden unintended decoupling and reinforcing the Trump Put, this de-escalation reduces the risk of a recession. We are lowering our 12-month recession odds from 50% to 30%. We now believe that the most likely path forward for the U.S. economy is a moderate stagflation where GDP growth slows below 1% but remains above 0%. Tariffs in the 10-12% range would increase the price level by a bit more than 1%, though there is a new wrinkle in the tariff inflation pass-through calculations. The recent depreciation of the dollar undercuts the traditional argument that dollar appreciation blunts the inflationary impact of tariffs. The trade-weighted dollar has in fact depreciated since the tariff announcements of March and April, and is now back to pre-election levels. Continued dollar weakness would therefore present an upside risk to our inflation expectations.

We believe this moderate stagflation implies a more hawkish path of monetary policy. While it’s true that lower tariffs mean less inflation, the roughly 1% increase in the price level we now expect from tariffs would still be large enough to spook the Fed. This is still the largest trade policy shock in a century. Recent history demonstrates that the inflation process during supply shocks is poorly understood, and the confusing manner in which the Trump administration is conducting this trade war muddies the waters even further. We don’t envy the retailer who has to set the price on a unit of inventory that had a 0% tariff when they ordered it and a 145% tariff when it arrived, while their competitor paid 30% because their boat arrived a week later. Opacity at the cash register, which the president is actively encouraging, will also make it harder for consumers to accurately identify the inflationary impact of tariffs, and harder for the Fed to gain confidence that tariff inflation is contained.

That uncertainty notwithstanding, it is the reduction in left-tail downside risk that will have the greater impact on the path of monetary policy. It is now less likely that the Fed will need to resort to recessionary rate cuts. Our modal expectation for below-potential growth still implies a gradual increase in the unemployment rate that will justify rate cuts. Those cuts will just begin later, proceed more slowly, and arrive at a higher terminal rate than we previously expected. The de-escalation of the trade war is welcome news for the U.S. economy, but it may not provide immediate relief for bond investors.