Trade policy uncertainty was the single greatest risk for the U.S. economy coming into Inauguration Day. President Trump has been talking about tariffs since the 1980s and continued in increasingly provocative terms on the 2024 campaign trail. Coming into 2025, we shared the consensus opinion that he would only deliver a small fraction of the extreme tariff increases he proposed. This is exactly what he did during his first term, raising the average tariff rate from 1.4% to 2.7%, far short of campaign proposals that would have raised it to nearly 20%. We anticipated that President Trump would raise the average tariff rate to something like 7-9% in his second term, a significant escalation from his first term but still well short of his most extreme campaign proposals.

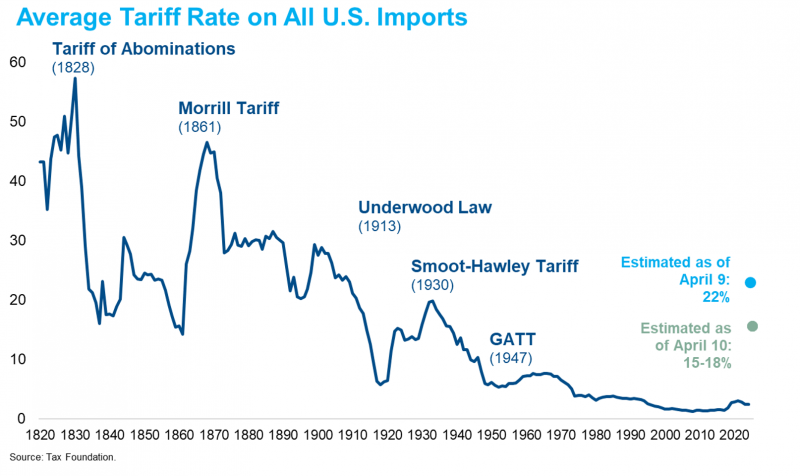

The tariff rates announced on April 2 were far higher than anyone expected and would have taken the average tariff rate to around 22% (estimating the average tariff rate becomes increasingly difficult the larger the increases because there is no precedent for how firms and consumers would respond). That would have been the highest tariff rate since 1909 and exceeded the infamous Smoot-Hawley Tariff of 1930. With imports to GDP 10 times larger than they were in 1929, these Liberation Day tariffs would have represented the largest trade policy shock in American history. They would have also amounted to the second largest effective tax increase on American consumers since WWII. Had those tariffs remained in place for any substantial period of time, we were confident that the U.S. economy would have fallen into a recession. The financial market volatility that ensued was justified, in our opinion, given this risk.

On Wednesday afternoon, President Trump announced a 90-day pause on most of these Liberation Day tariffs in favor of a 10% universal tariff, while also simultaneously raising tariffs on China to 125% (in retaliation for their 84% tariffs). The average tariff rate is calculated as total tariff revenue divided by total imports. Estimating the average tariff rate under a 125% / 84% regime is nearly impossible as imports would drop sharply and the tariff revenue would never materialize. There is no modern precedent for the sudden imposition of tariffs this high between two nations with a substantial trading relationship. Our best guess is that the average tariff rate would settle around 15-18% after accounting for the reduced imports. That rate is lower than Liberation Day, but far higher than we expected at the start of the year.

Tariffs inject a stagflationary impulse. The current policy would significantly raise inflation and slow growth, potentially enough to cause a recession. The challenge is that nobody knows how long the current policy will remain in place. The events of the last two weeks have made clear that the key variable for assessing the U.S. economic outlook is not the mechanical impact of the tariffs themselves, but rather the president’s resolve in maintaining those tariffs in the face of the financial market and economic volatility they cause.

We reduced our 12-month recession odds to 20% after the election in November on the logic that the anti-growth effects of trade and immigration restrictions would be more than fully offset by the pro-growth effects of tax cuts and deregulation. We raised those odds to 40% after the Canada/Mexico tariffs were implemented in early March, and then to 60% after the Liberation Day tariffs as rhetoric from administration officials suggested they were willing to bear significant economic turmoil in pursuit of their stated objective to fundamentally transform the global trading system (or perhaps reducing bilateral trade deficits?). The 90-day pause suggests either less willingness to bear that turmoil or a more modest objective of reform to existing trading relationships. We, therefore, now lower our recession odds to 50% as the path to further reductions to current tariff levels now appears slightly wider.