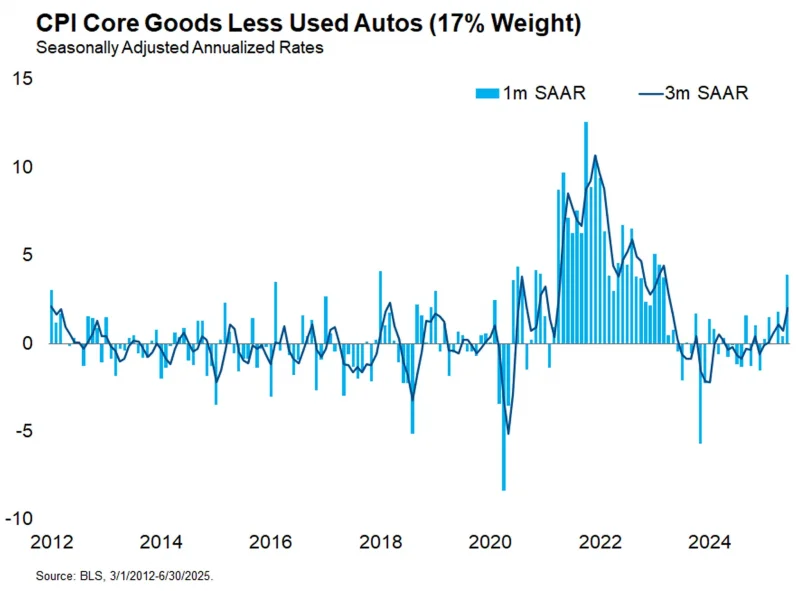

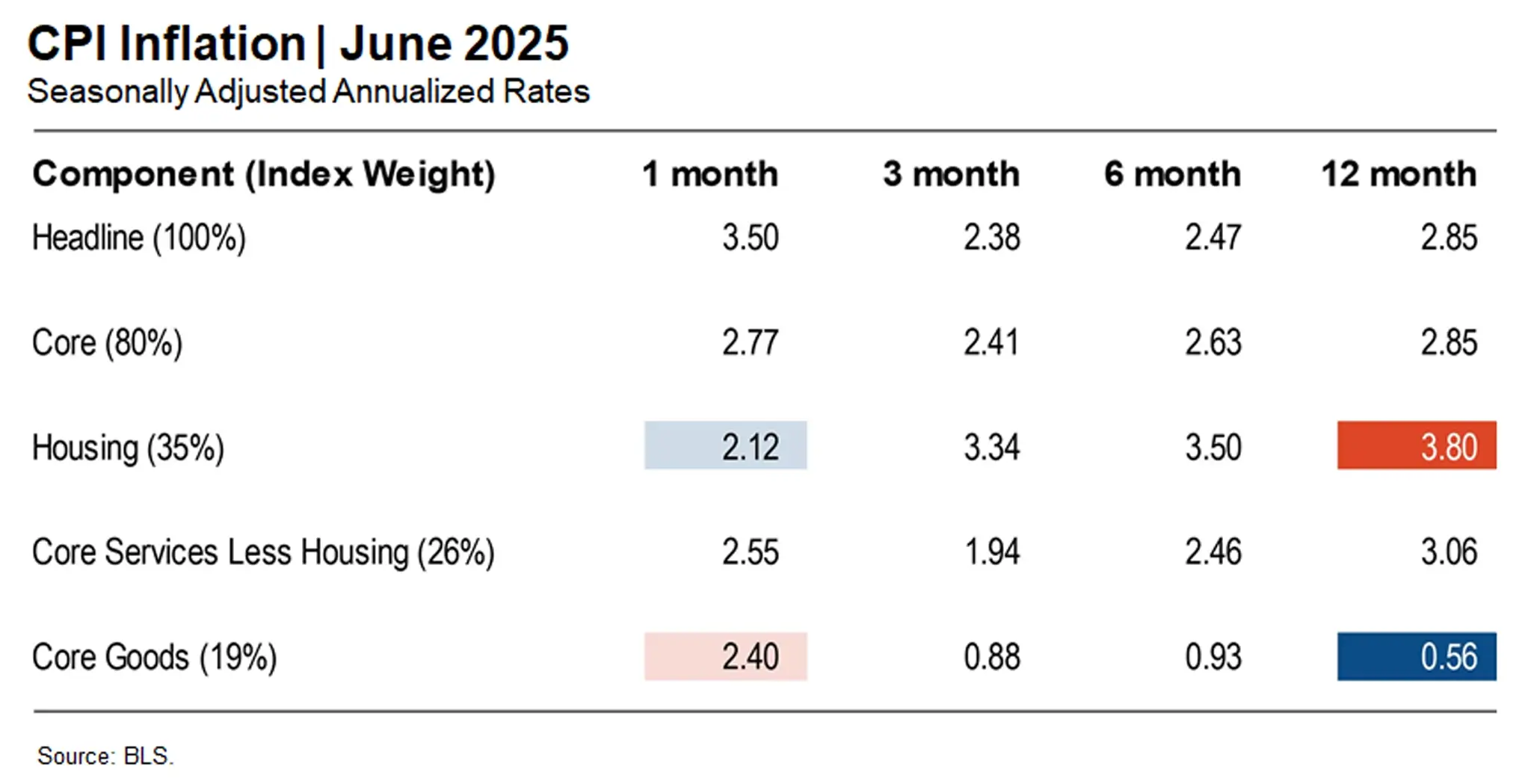

Tariff inflation made its highly anticipated debut in the June CPI report. Core CPI increased at a 2.77% annualized rate in the month, slightly above the pace of recent months. This figure was held down by continued disinflation in housing prices, which rose at a 2.12% annualized rate in June, the lowest monthly pace since February 2021. Core services less housing printed within recent ranges at 2.55% annualized. The action was in core goods prices, which rose at a 2.40% annualized rate in the month.

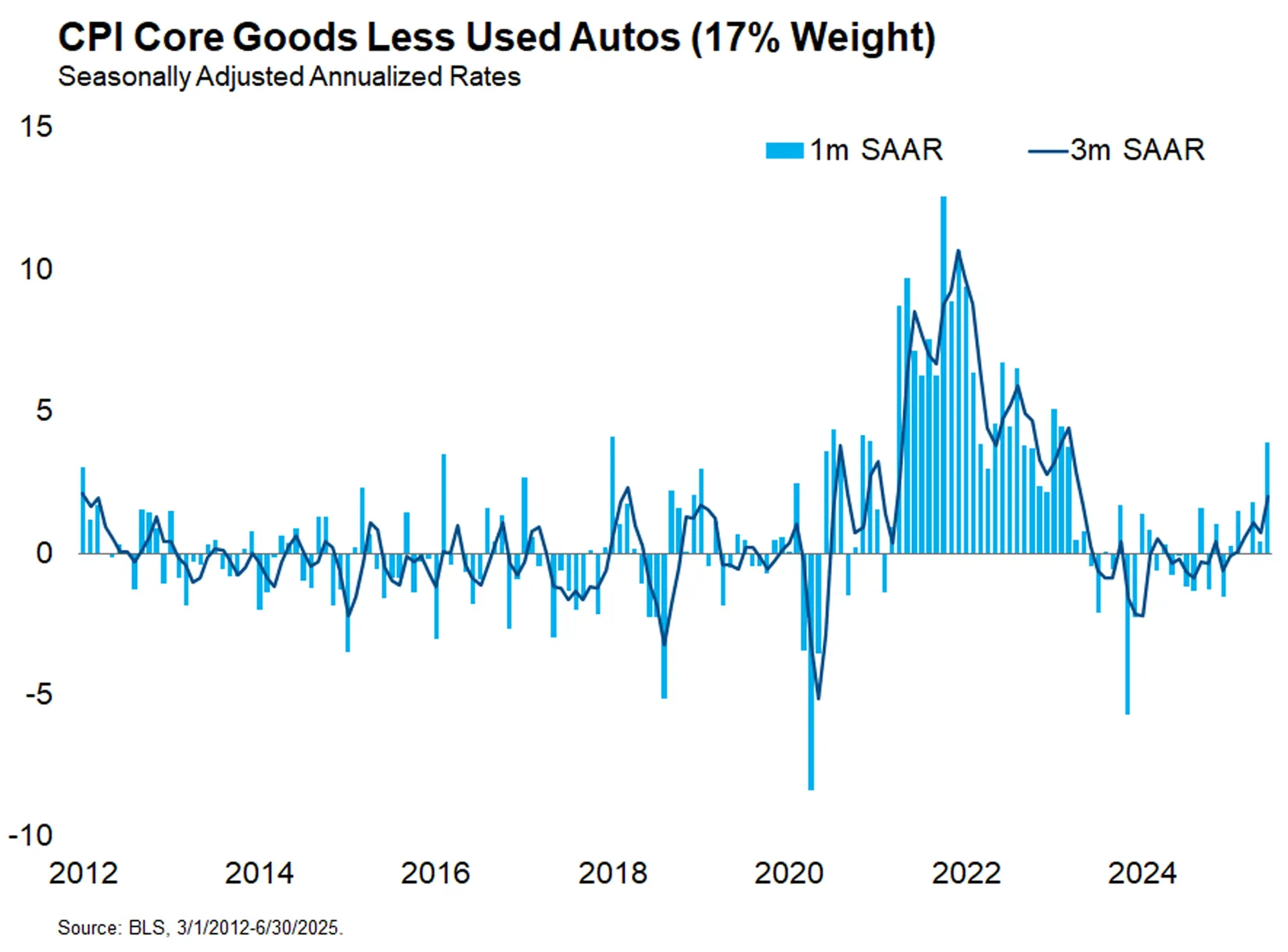

Core goods inflation was held down by significant deflation in used car prices, which are typically volatile and only indirectly exposed to tariffs. Core goods excluding used autos rose at an annualized rate of 3.92% in June and 2.02% over the trailing three months. Those might not sound like very high inflation rates, but remember core goods have flirted with outright deflation in the two decades prior to the pandemic as globalization drove down the prices of many manufactured goods. Prices in this category, core goods less used autos, increased by less than 1% cumulatively from 2000 to 2019. The 3.92% annualized rate in June would rank as the fifth highest monthly rate in those two decades (2000-2019).

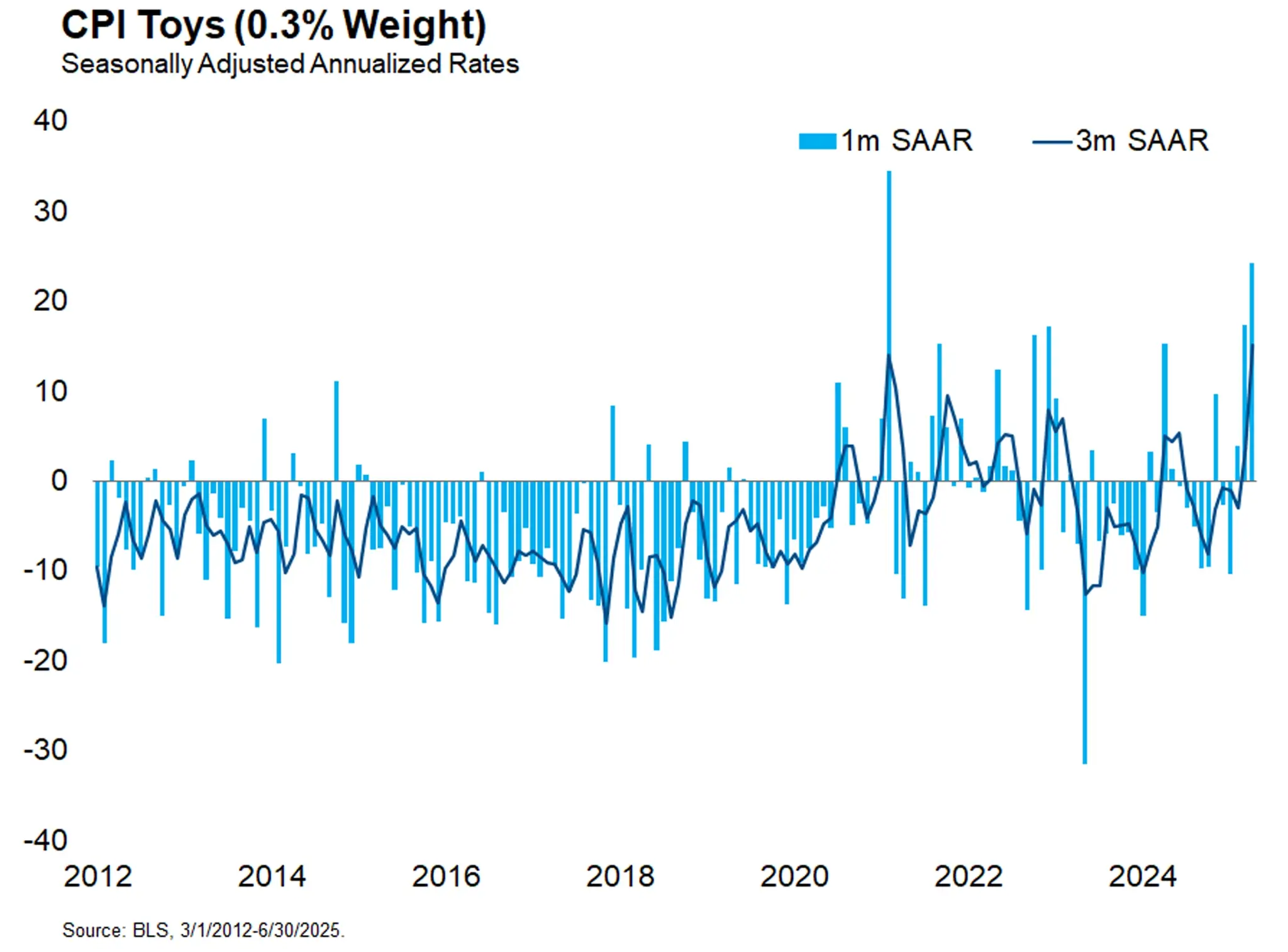

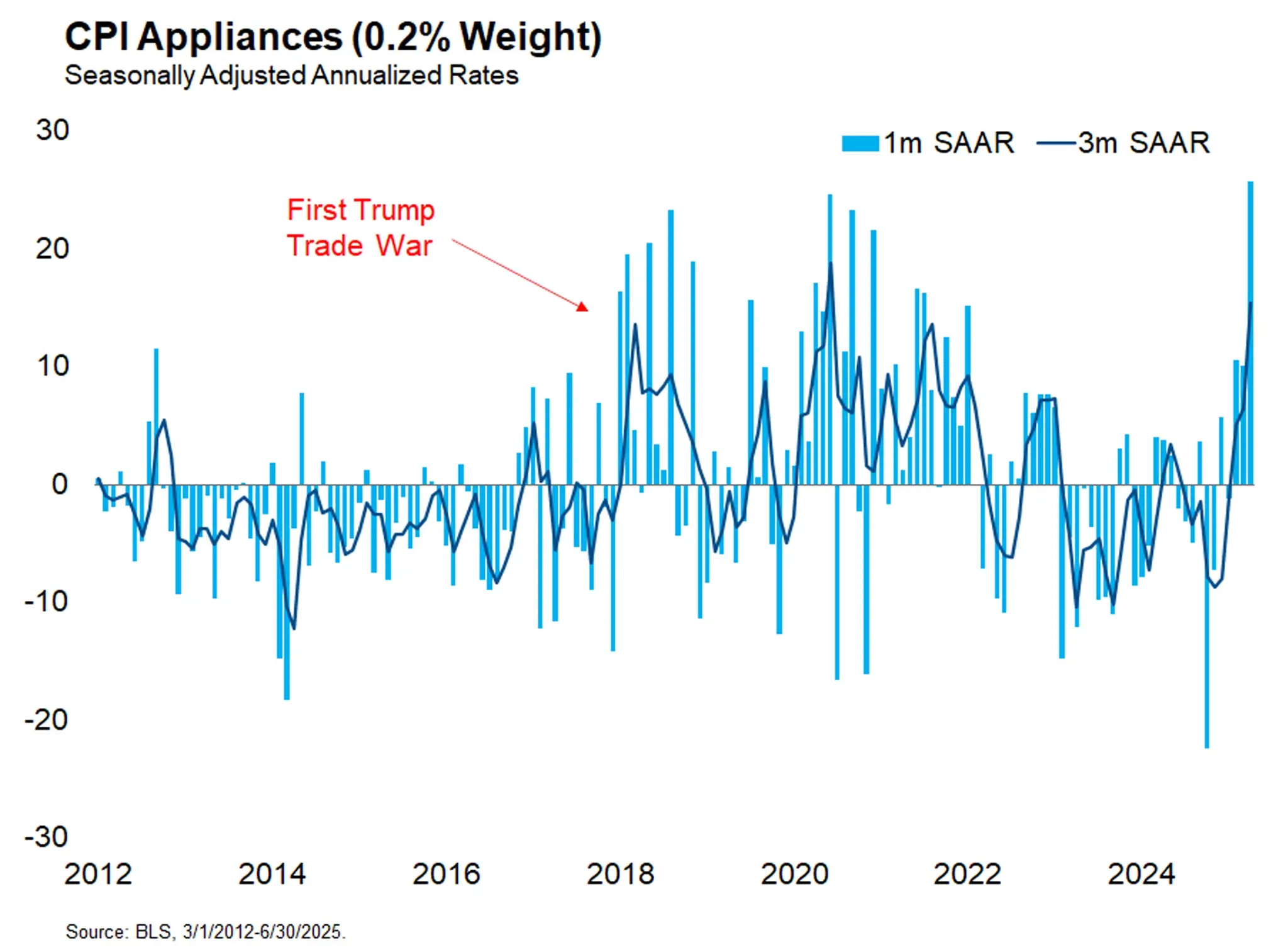

We can zoom even further into the core goods category to see a more decisive tariff impact. Toys and appliances are two product categories where the vast majority of consumption is imported – mostly from China. Prices for these two products rose at their first or second fastest monthly pace in two decades. Appliances are especially instructive because they were directly targeted with sectoral tariffs during President Trump’s first term, and exhibited clear pass-through effects from tariffs two years before the pandemic set inflation alight across the goods sector. That tariff inflation episode followed a 25% cumulative deflation in appliance prices between 2000 and 2017 (the Trump tariffs were announced in January 2018).

If you’ve been reading the charts above closely, you may have noticed that the weights of these components are fairly small. Toys and appliances together sum to just half a percent of the CPI – we highlight those categories because they are so reliant on imports. All core goods account for just 19% of the index. Imported goods only account for about half of that, or 10% of the total consumption basket. The U.S. has a fairly closed economy relative to our peers (imports as a share of consumption are about twice as high for the average OECD member than for the U.S.). Imported goods just aren’t that important to our services-dominated economy. That’s why we never believed that the mechanical effects of the tariffs alone were enough to tip the economy into a recession. That outcome would require a more substantial deterioration in business sentiment, which seemed more likely in early April but less so now that President Trump has demonstrated a willingness to deescalate.

The primary impact of tariff inflation in our opinion is to delay further easing by the Fed. Chairman Powell has told us that the Fed would already have cut rates in June if not for tariffs. While we do expect that tariffs will cause a meaningful increase in the prices of imported goods, their small share translates to a manageable 1.0-1.5% increase in the price level, briefly taking core CPI north of 4% in the second half of this year. We agree with Governor Waller’s presumption that this tariff inflation will most likely take the form of a transitory one-time increase in the price level as opposed to a persistent inflation problem. But we believe that it will take several more months for a majority of the FOMC to confirm that hypothesis. We are fairly certain that the FOMC will not cut rates at their July meeting as Waller recommends. After that, the Fed gets to see two more CPI prints before their September meeting. We continue to believe that those prints will show enough tariff inflation to delay the cut beyond September, but we’ll be closely monitoring those data releases as they come in.