As the (seemingly) never-ending search for yield continues in year eight of the “low for long era,” an oldie but a goodie comes to mind. The cash and carry trade, which undoubtedly raises fond memories from your “Intro to Derivatives” course, has caught our eye recently.

As a brief reminder, a cash and carry trade is when an investor purchases a security and simultaneously sells it forward at a specified price. Since she both owns the security and sells it forward, she has no exposure to the underlying security. Instead, she earns a carry (the difference between today’s purchase price and the higher future sales price) on the cash she has invested.

Why do we bring up this textbook trade now?

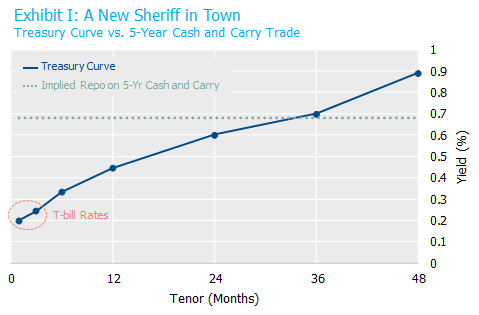

Well, for some time, the carry (aka implied repo) on purchasing Treasury bonds and selling them forward via Treasury Futures has been well above T-bill/Short Term Investment Fund rates. The chart below shows the implied repo on the 5-year cash and carry trade (68 bps) vs. the Treasury curve. Currently, an investor earns approximately 45 bps more than T-bills in this strategy. Put differently, she would have to extend her cash by nearly 3 years in maturity (and accept the corresponding market risk) to receive the same yield in the Treasury market. Alternatively, if she purchases A1/P1 commercial paper, with the associated credit risk, she currently receives a yield premium of only 25-30 bps over T-bills.

Source: Bloomberg as of 06/27/16.

Source: Bloomberg as of 06/27/16.

Why is there this return difference on two strategies with such similar risk profiles?

Institutional reasons abound. For example, standard money market funds are generally precluded from owning securities longer than 13 months to maturity, hedged or not. In addition, money market funds generally have limits on weighted average maturity and weighted average life – e.g. 60 and 120 days, respectively. These restrictions, and a general demand for simple liquidity, have pushed T-bill rates to include a premium for being “dear,” in our opinion. In addition, the recent spate of regulatory changes on Wall Street has reduced dealer balance sheets, making certain securities (like those necessary to arbitrage this relationship) relatively expensive to hold from a required capital perspective. So, players that historically would drive the relationship between implied repo and T-bill rates closer to one another are largely sidelined.

This yield advantage of cash and carry over T-bills currently holds true across multiple futures contracts, with some contracts offering higher implied repo rates than others.

While the futures and bond are traded as a package, eliminating market slippage risk, there are additional risks that accompany the cash and carry trade that are worth noting. A few selected examples: Unwinding the trade before expiry would incur annualized transaction costs of about 3 bps. Also, if the implied repo rate becomes larger prior to futures expiry, it would create a negative mark-to-market during the holding period. (For example, a 10 bps increase in the implied repo rate on a $100mm trade would result in approximately 2.7 bps of negative MTM. But in fairness, this is the same economic risk a T-bill holder bears with respect to changing T-bill yields.) Another wrinkle is that cash is generally required to facilitate mark-to-market on futures variation margin, if needed. A further 0.5% – 2.5% is needed to post as initial margin, which in the (very unlikely) event of an FCM insolvency is potentially at risk.

For investors hungry for extra returns, however, this additional complication may be worth the enhanced yield over T-bills.