For several months now, many of us have been wondering: why hasn’t anything blown up yet? The Powell Fed’s historic tightening campaign has caused relatively few episodes of financial distress (with the notable exception of crypto). The sudden failure of the nation’s 16th largest bank – the 2nd largest bank failure in American history – has put that question to rest. The demise of Silicon Valley Bank and the immediate regulatory response have shaken financial markets, causing an 89-basis-point decline in the 2-year Treasury yield in two days, the largest two-day decline since Black Monday in October of 1987. In this note, we will review the tumultuous events of the past few days and consider the contagion risk to the regional banking system.

What went wrong at SVB

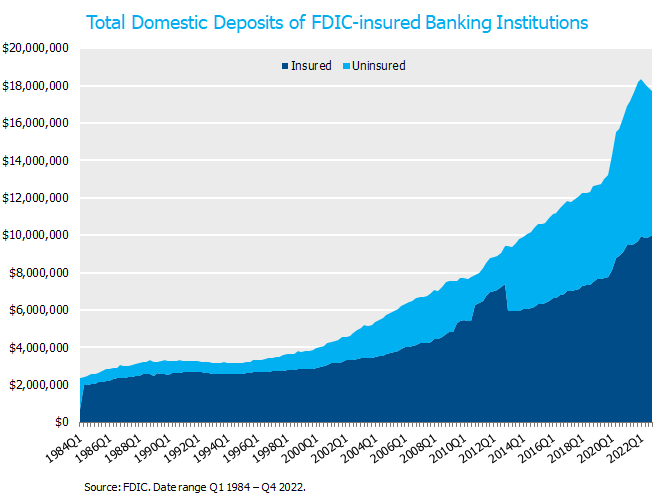

Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) was very much a creature of the financial conditions created by the Fed and fiscal policymakers. The bank has been around for 40 years, but the excessive monetary and fiscal stimulus during the pandemic created a flood of easy money. SVB’s deposits tripled from $62 billion to $198 billion between December 2019 and March 2022, compared with a 37% increase in deposits for the total banking system. Even worse, 96% of SVB’s deposits were not insured by the FDIC (because account balances were in excess of the $250,000 FDIC insurance limit). For the entire banking system, 44% of the $18 trillion in domestic deposits are uninsured. SVB was a notable outlier in this regard.

Rapid growth alone is not enough to cause a bank failure. Two other conditions were necessary for SVB’s demise, both related to the Fed’s tightening cycle.

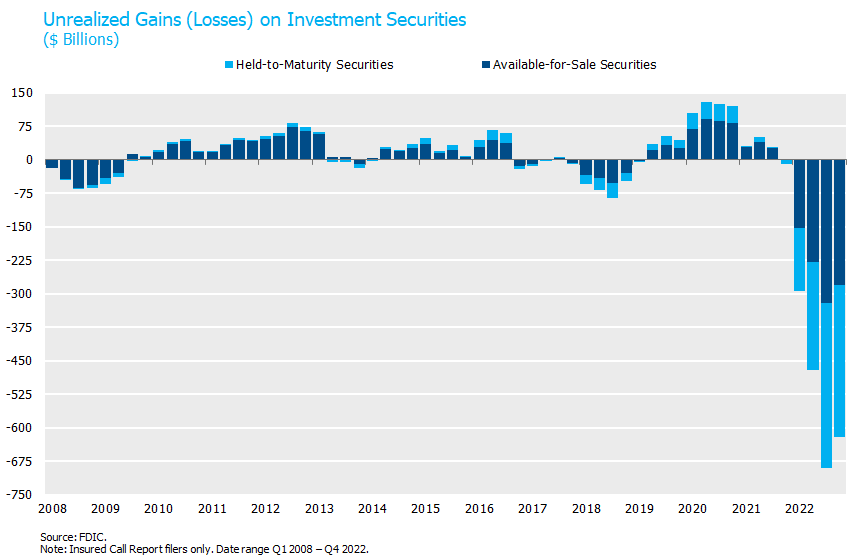

First, SVB invested the vast majority of those pandemic deposit inflows into medium-duration Treasuries and MBS. We cannot know for sure management’s intention of doing this and whether it was an attempt to capture additional term premium or potentially a miscalculation around how well its securities portfolio and liabilities (e.g., deposits) were matched. However, it is clear that they effectively bought at the top of the bond market. Once the Fed began their historic tightening campaign, SVB’s investment portfolio got hammered. In fact, their unrealized losses were so large that they exceeded the total equity capital of the bank.

Second, SVB’s deposit base was highly concentrated among startup tech companies, their founders and their venture capital backers. The Fed’s 2022 tightening campaign closed the spigot of fresh capital inflows into tech startups and caused cash to become dear. SVB was initially able to fund the resulting deposit outflows, but last week the trickle of outflows became a torrent when several prominent VC firms advised their portfolio companies to withdraw their funds. SVB tried a last-ditch effort to sell securities and raise equity to fund these outflows, but on Thursday alone, depositors attempted to withdraw $42 billion. To the extent management had made an assumption around the duration and persistency of deposits in extending the securities book duration, this assumption proved incorrect. The bank run was underway and SVB was in FDIC receivership within 24 hours.

Contagion risk

In short, we believe SVB was a unique case of a bank with an unstable deposit base and foolish managers who made an ill-timed bet on interest rates. Whether other regional banks are susceptible to similar risks will depend in large part on two questions:

- How big are the losses on bond portfolios?

- How susceptible are banks to a run on uninsured deposits?

SVB had exceptionally bad timing in buying the top of the bond market, but they are certainly not the only bank who has taken losses on their investment portfolios. Aggregate unrealized losses across the entire FDIC-insured banking system totaled $620 billion as of year-end (note the contrast with 2008, when a surge in Treasury prices mostly offset losses in other securities). That’s a big number, but not as scary relative to the size of the banking system, which has total assets of $24 trillion and total equity capital of $2.2 trillion. $620 billion is surely enough to put a dent in bank balance sheets, but to our knowledge, SVB was the only bank of material size where unrealized losses exceeded equity capital.

How stable are uninsured deposits?

FDIC deposit insurance was created during the Depression as a way to reduce the risk of bank runs. A depositor is an unsecured creditor to a bank, but if their deposit is guaranteed by the government then there is no need to worry about credit risk and no need to join the queue during the bank run. The flaw in this system is that some deposits are not insured. As stated previously, FDIC-insured banks had $18 trillion in total deposits at year end, of which $10 trillion or 56% were insured. That ratio is down from around 75% in the early 1990s.

As the fate of SVB instructs, uninsured deposits remain susceptible to a run. This proved fatal in the case of SVB because 96% of their deposits were uninsured. To our knowledge, no other bank of material size has such a large share of uninsured deposits (we include the “material size” disclaimer because there is a long tail of tiny banks among the 4,700 FDIC-insured institutions in the nation).

The policy response

As of last weekend, it was impossible to know whether Monday would bring a broader run on the $8 trillion in uninsured deposits across the banking system. Regulators decided on Sunday evening that they were not willing to find out, a judgment call that we will surely be debating for years to come. Regulators announced two primary actions on Sunday evening:

- Secretary Yellen, with the approval of Chairman Powell and President Biden, invoked a systemic risk exception to guarantee all insured and uninsured deposits of SVB and a second bank, Signature Bank (with $100 billion in assets, about half the size of SVB). This is a new authority created under Dodd Frank, where any losses to the Deposit Insurance Fund will be covered by a special assessment on FDIC member banks rather than U.S. taxpayers.

- The Fed created a new emergency lending facility, the Bank Term Funding Program (BTFP). Banks can pledge Treasuries, MBS and other qualifying assets to BTFP as collateral for a one-year loan at a rate of 1-year Overnight Index Swap (OIS) plus 10 basis points. Importantly, these assets will be valued at par rather than market value.

Will it work?

Whether this policy response will prove effective in averting a regional banking crisis is of course the $24 trillion question everyone wants answered. We don’t have a crystal ball, but this policy response strikes us as very forceful and directly targeted at the two questions we raised above. Though the BTFP facility does not wipe away the $620 billion in unrealized losses that banks were carrying on their investment portfolios, banks no longer need to sell bonds in the market at 85 cents to fund deposit outflows. Instead, they can simply pledge them to the Fed and receive 100 cents.

The decision to make whole the uninsured depositors of SVB and Signature was clearly intended to send a message and reduce the risk of a broader deposit run. Repaying in full the uninsured depositors of the two failed banks is clearly designed to reduce the risk of uninsured deposit flight at other banks. This is the greatest source of uncertainty regarding the future course of events. If we take this weekend’s policy actions as precedent, then regulators have implicitly guaranteed all $18 trillion in deposits in the banking system. (In typical fashion, they have stopped short of making this guarantee explicit).

In our view, these policy actions should be effective in reducing depositors’ incentive to pull their uninsured deposits from regional banks. But it remains possible that some depositors may do so out of an abundance of caution. After all, what’s the downside of moving your cash to a larger bank or into Treasury bills? Whether this happens or not will go a long way to determining the risk of contagion to other regional banks. We remain optimistic, but predicting this outcome would require seeing into the minds of millions of depositors across the nation. S&P downgraded First Republic Bank this morning from A- to BB+, specifically citing the risk that deposits would flow out despite the regulatory actions, so this question is clearly front of mind for market participants.

Let us conclude on a positive note. Regulations implemented since 2008 have created a much more resilient and better-capitalized banking system. The contagion risks described above are almost entirely limited to regional banks, and we are optimistic that even that outcome will be avoided. The largest banks in the nation are so well capitalized and have such stable deposit bases that they are nearly immune from either uninsured deposit flight or insolvency resulting from securities losses, unless the economic environment deteriorated significantly. We have come a long way since 2008. We’ll have more to say about the many implications of this week’s events (for the path of monetary policy, the future of bank regulation, etc.). In the meantime, feel free to reach out with any questions you may have about these broader topics or your specific portfolios.