Jobless claims data corroborate our assessment of the low-hiring, low-firing state of the labor market. We economists love the jobless claims data for two reasons. First, the data are collected via hard count of actual unemployment insurance claims, not a survey subject to sampling bias, estimation methods, etc. Second, the data are high frequency, published every week and arriving sooner than the monthly and quarterly labor market statistics.

Recent revisions in the payrolls report do not give us any reason to doubt the accuracy of that data, but it is always best practice to consume all sources of data to gather the most comprehensive view on the state of the economy. In this case, the jobless claims data appear entirely consistent with other data sources and the low-hiring, low-firing state of the labor market we have described since last year.

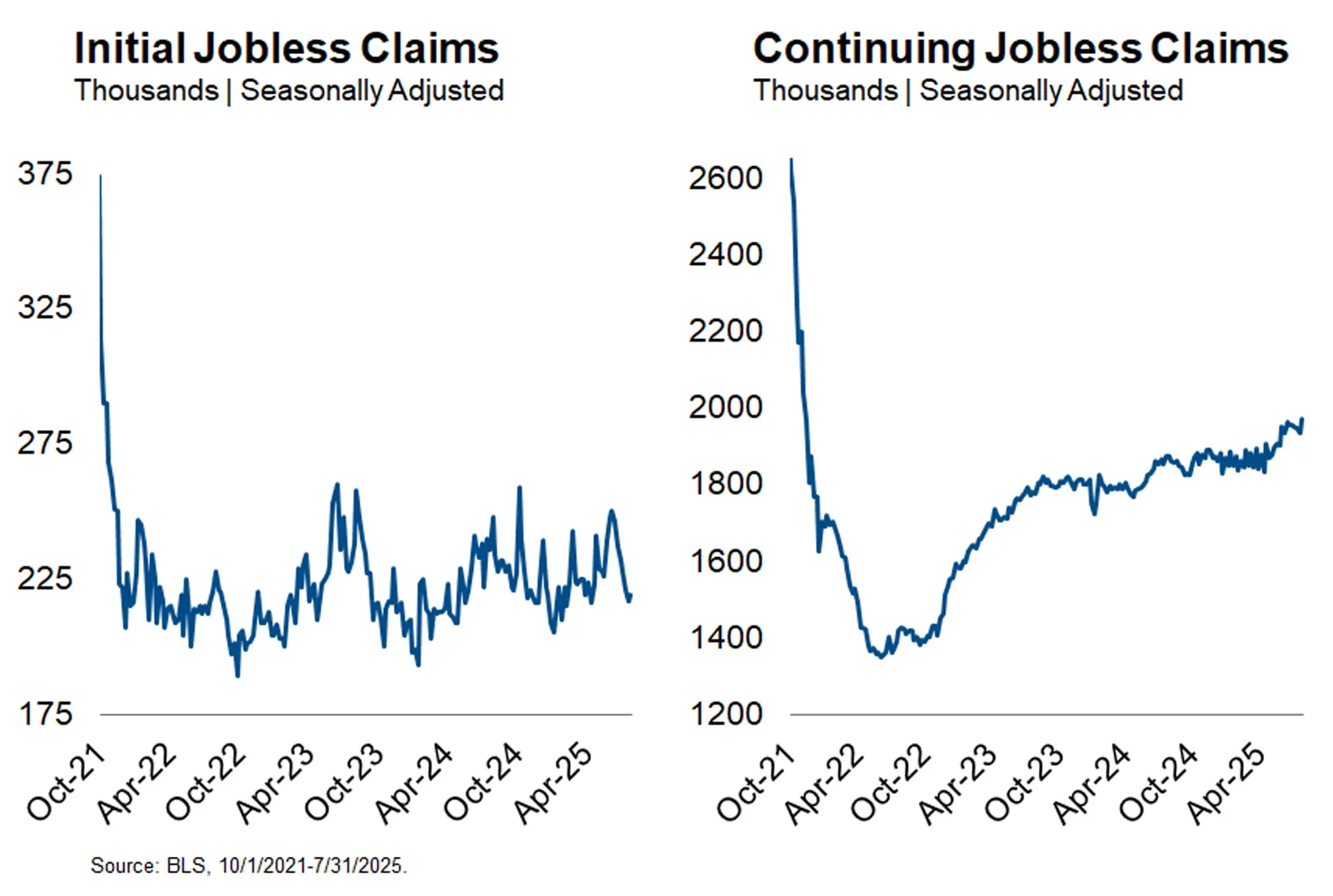

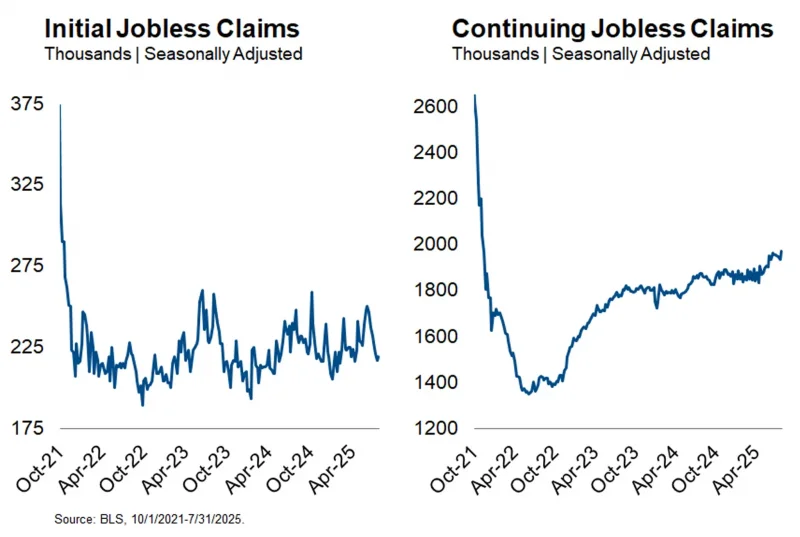

The initial jobless claims series is a flow measure that counts the number of new claims filed each week. This series has remained very low since late 2021, indicating that there has not been a significant increase in layoffs. The most recent reading of 226,000 sits at the 12th percentile of all observations since 2000. The labor market has not crossed the tipping point from reduced hiring to layoffs that is typical during recessions. Economists watch closely for sudden increases in initial claims as an early warning indicator of recessions, but no such spike is evident today.

The continuing jobless claims series is a stock measure that counts the number of claims filed by individuals already receiving unemployment insurance in the prior week. This stock measure has climbed very gradually since early 2024 and sits at a cycle high of 1.974 million in the latest release (the 25th percentile of all observations since 2000). The combination of low inflows (initial claims) and a gradually rising stock (continuing claims) tells us that more workers are getting stuck on unemployment insurance for a longer time. The two most common causes of outflows from unemployment insurance are re-employment and exhaustion of benefits (most states offer 26 weeks of benefits).

In the current moment, a declining re-employment rate is the most likely culprit for the gradual increase in continuing claims. This assessment is supported by the low hiring rate in JOLTS and the low re-employment rate in the labor force flows data. This is a good labor market if you have a job. It is not a good labor market if you’re looking for a job. Low layoffs have prevented a sudden spike in unemployment insurance claims, but low hiring has allowed for a gradual increase and left the labor market with very little cushion to absorb any further decline in labor demand.