Hedge funds often use hurdle rates that are low—and often zero—to measure portfolio performance. Moreover, returns above these hurdle rates incur performance fees that can, at times, exceed 20%. At a minimum, we believe hurdle rates should match the prevailing interest rate; otherwise, investors end up paying performance fees for cash returns. If these returns are indeed true alpha and not beta in disguise, these fees may be justified. However, earning a cash rate is not alpha. So why should a hedge fund manager be able to charge a performance fee for earning returns that can be achieved by simply purchasing a T-bill?

Since the Fed began increasing the Fed funds rate in March 2022, which peaked at 5.25% before settling at 3.75% today, a capital commitment to a hedge fund can earn comparable rates by purchasing a T-bill. For example, a hedge fund with a management fee of 2% and a performance fee of 20% that just bought a 5% yielding T-bill would result in total fees of 2.6% with 2.4%[1] net, assuming no fund or pass-through expenses, paid to the investor. More than half of the total return is consumed by fees, resulting in a negative alpha on a net-of-fee basis, despite achieving a positive absolute return. Of course, if that were all the hedge fund did, investors would eventually leave and those hedge funds would not be in business long. Although with a 2.6% fee for a T-bill return, the hedge fund doesn’t need to be in business long to end up happy!

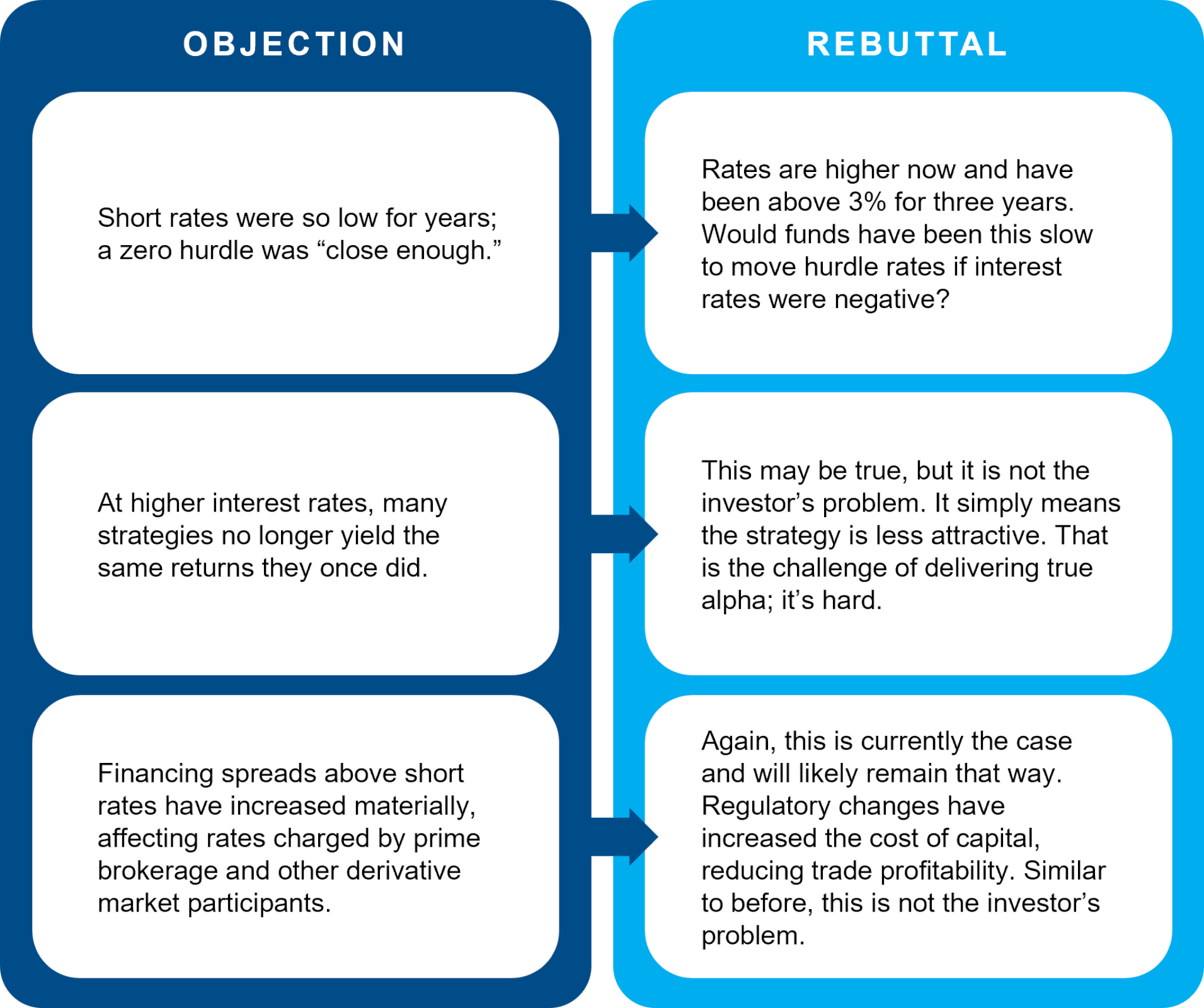

Anecdotally, we have heard a variety of reasons why hurdle rates should be zero or, at the very least, below the T-bill rate. We have yet to hear one that withstands scrutiny. Below are three examples.

Hurdle Rate Objections—and Why They Don’t Hold Up

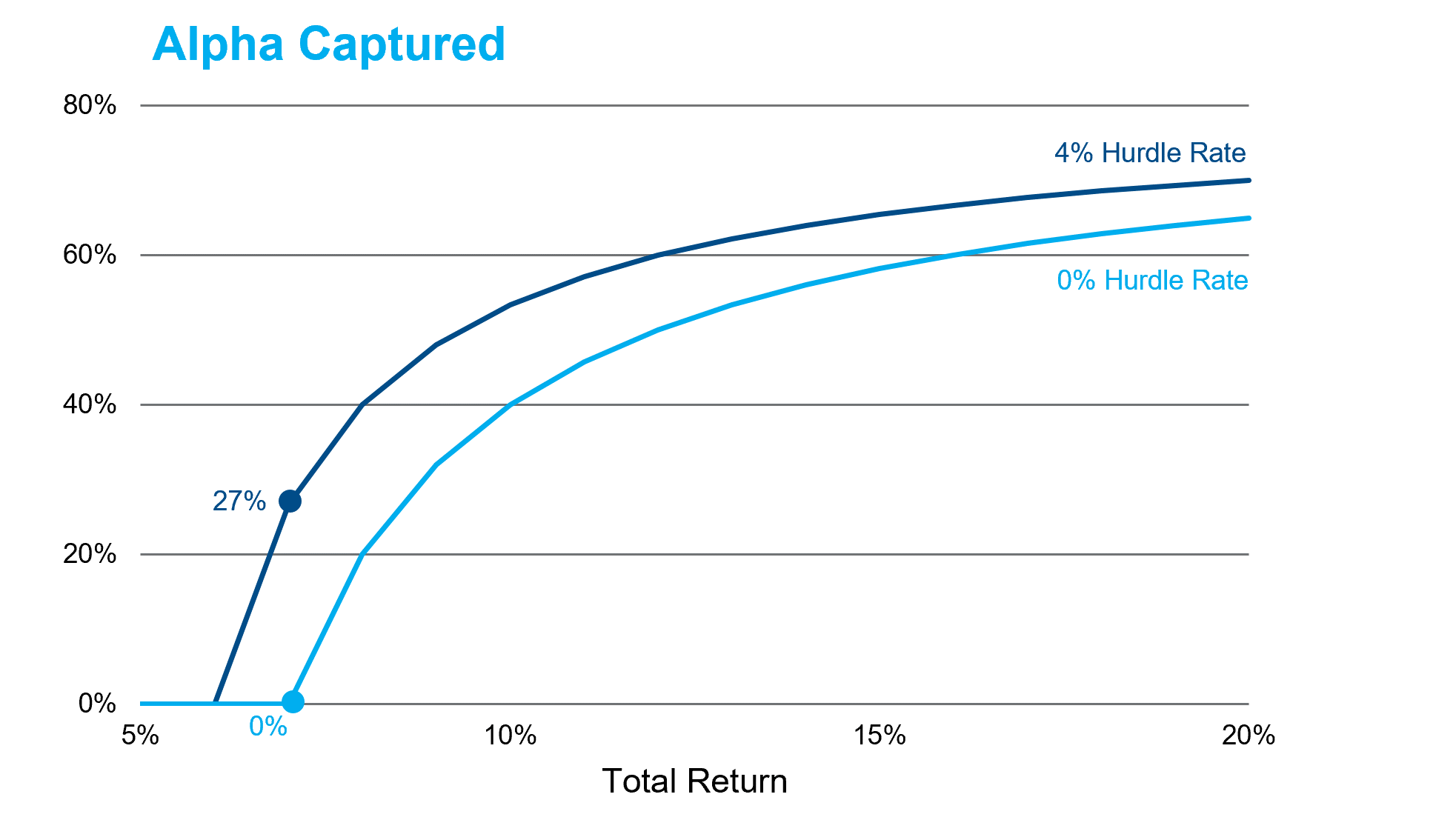

The underlying theme is straightforward: many hedge funds collect performance fees on the cash return, but let’s look at it through a few different lenses. A 0% hurdle rate significantly alters the effective performance fee and the share of investor alpha. Figure 1 shows the impact of different hurdle rates on investor performance, assuming a 2% base management fee and 4% T-bill rate. As depicted, a hedge fund with a 7% total return and a 0% hurdle rate collects 3% in fees (2% base fee + 1% performance fee), leaving investors with zero alpha. Alternatively, setting the hurdle rate to the T-bill yield reduces the performance fee from 1% to 0.2%—a 27% alpha capture ratio (0.8% alpha after fees / 3% gross alpha) for investors.

Figure 1: Zero Hurdle, Less Investor Alpha[2]

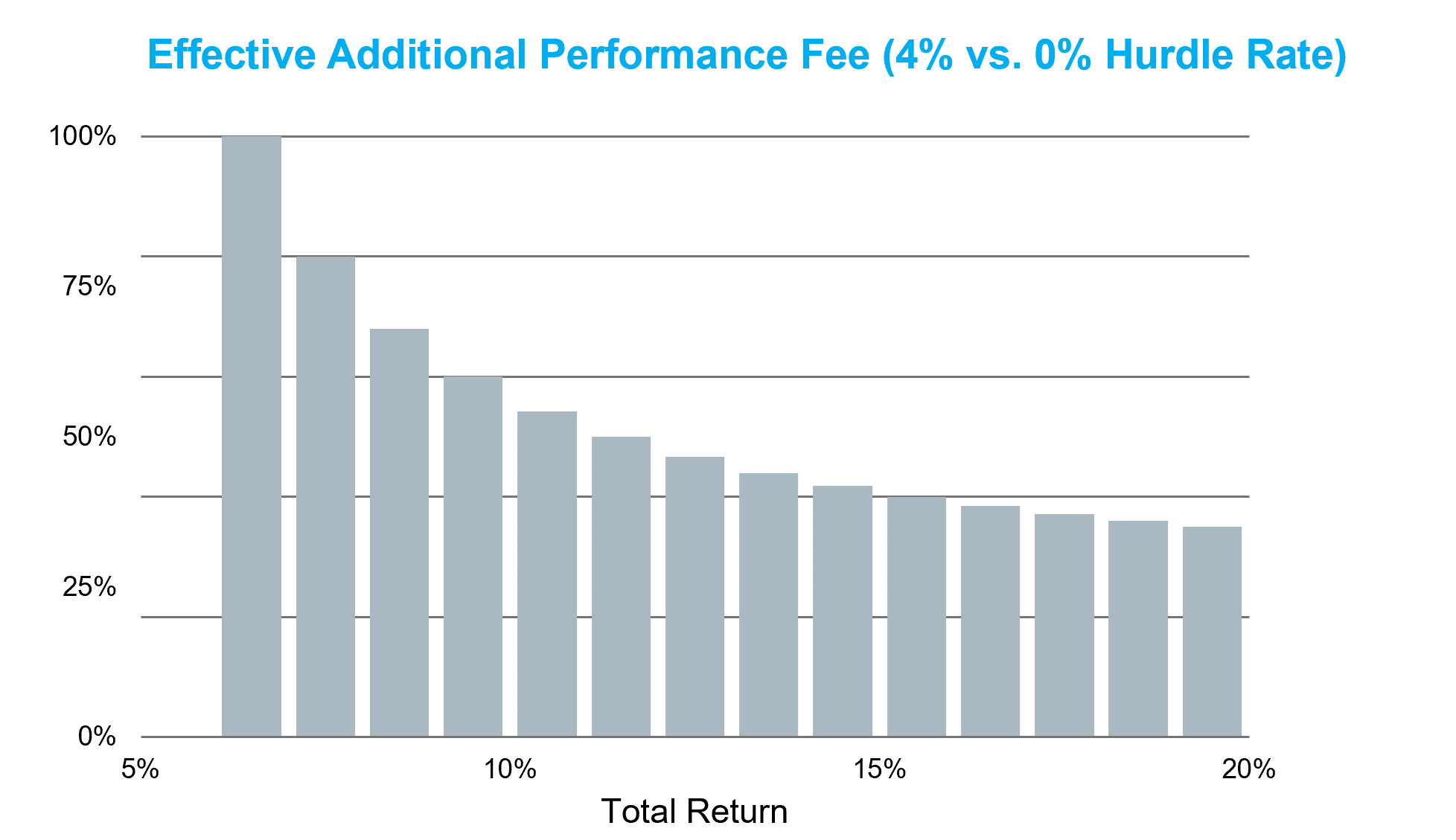

A different lens for viewing hurdle rates is to translate them into an effective performance fee. Figure 2 represents the performance fee that would make hedge fund managers indifferent between a “2 and 20” fee with a 0% hurdle rate versus a “2 and X” fee with a 4% hurdle rate. At a 7% return, the breakeven is a 100% performance fee! At higher returns, the breakeven falls to 25-35%. This wedge represents the impact of a 20% performance fee on the T-bill yield, in our example, 80 bps. An artificially low hurdle rate is just a performance fee in disguise.

Figure 2: The Cost of Easy Performance Targets

As hedge funds seek longer lockups, higher incentive fees and broader pass-through expenses, collecting a performance fee for buying T-bills takes egregiousness to a new level. Moreover, the arguments for low hurdle rates are superficial at best, challenge believability and turn a hedge fund problem into an investor problem. If you are paying performance fees, hedge funds should have to jump at least a little to clear hurdles.

[1] 2% base fee + (3% X 20% performance percentage) = 2.60% total manager fee.

[2] We have intentionally floored the alpha capture ratio at 0%.