Spare a thought for your local financial economist today. The shutdown has deprived us of BLS data and our favorite day of the month spent digging through the details of the U.S. labor market. We are left no choice but to resort to second-tier and alternative sources of labor market data. They do not paint an encouraging picture as we await the reopening of the BLS.

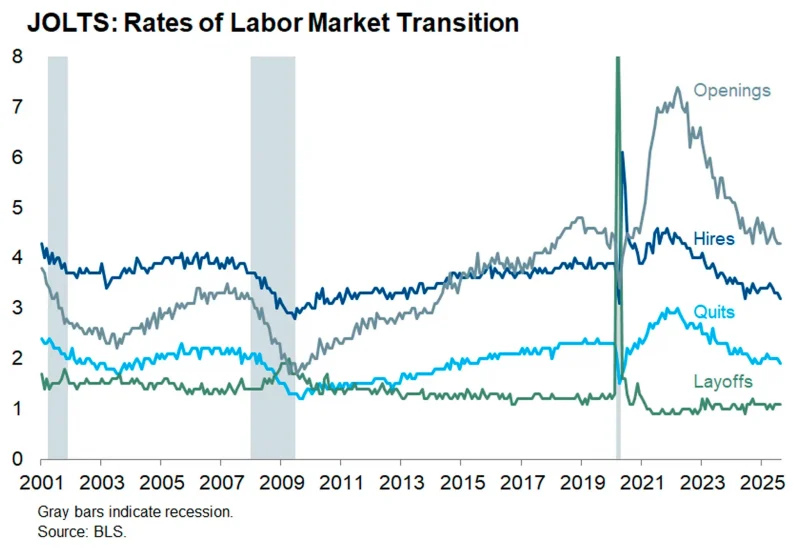

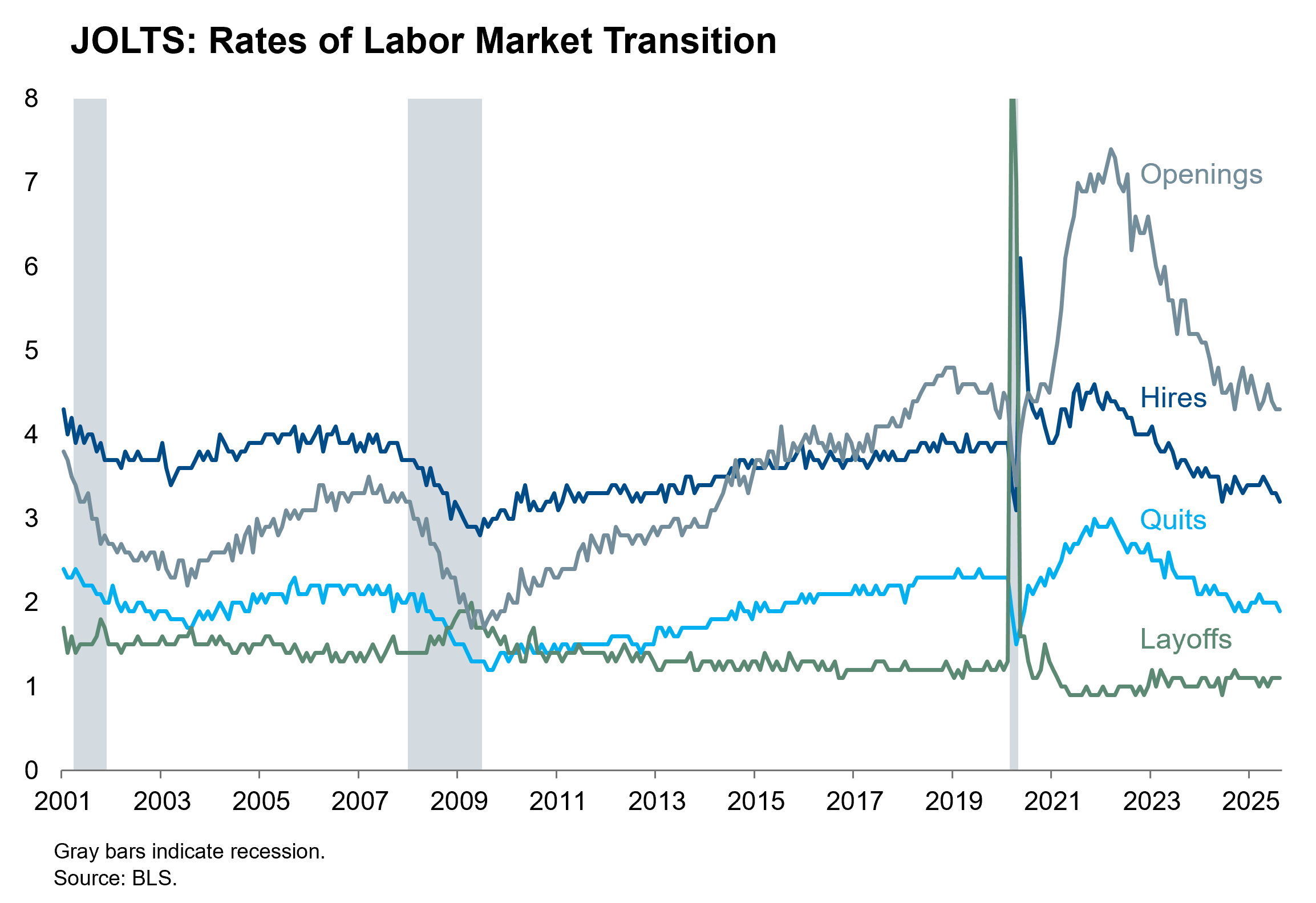

The August JOLTS report released before the shutdown revealed a continued softening in labor conditions. Though the layoffs rate remained low, the rates of openings and hires ticked down to cycle lows. Labor demand continued through August on the weakening trend that has prevailed since late 2021. The quits rate likewise matched its cycle low as workers themselves recognized the difficult hiring environment. Recent surveys are consistent with the August JOLTS data. The employment components of the ISM Services and Manufacturing Reports remained below 50 in September, suggesting weak labor demand. Consumers also expressed their pallid view on job availability in the Conference Board Consumer Confidence Survey, where the labor differential component fell to a new cycle low.

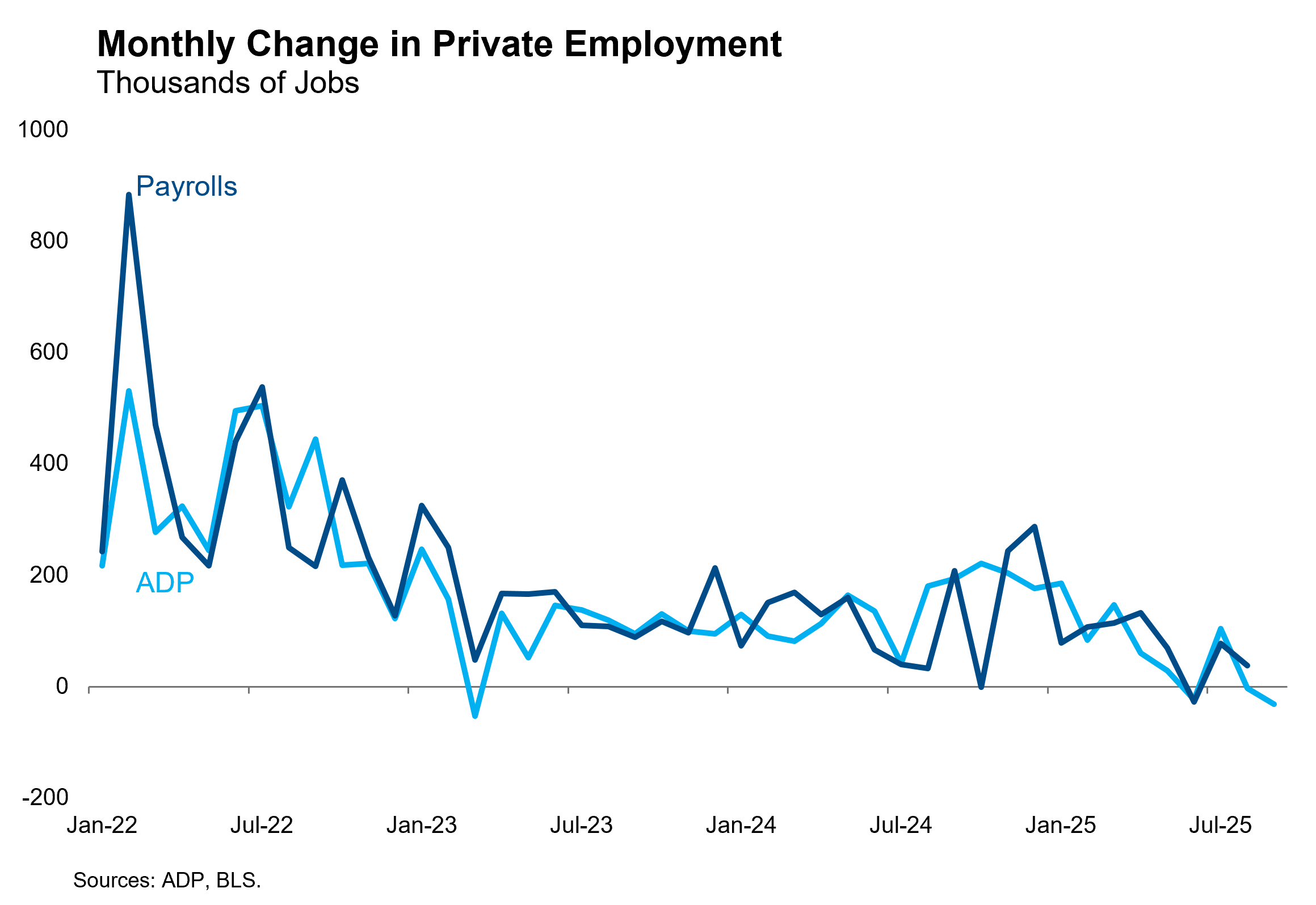

The ADP employment report estimated a 32,000 decline in private nonfarm payroll employment in September. Much to forecasters’ chagrin, the ADP figure is not a reliable predictor of a single monthly nonfarm payrolls number from the BLS – there is simply too much noise in both measures. But the two series do correlate well over longer timeframes, and the downtrend has now taken the ADP figure into negative territory for three of the last four months.

With a stroke of fortuitous timing, the Chicago Fed recently released a new labor market dashboard that distills official and private data sources into a forecast for key indicators. The first release forecasts that September will show a decline in the hiring rate, an increase in the separations rate, and an increase in the unemployment rate — in short, a continuation of the softening trends observed in the official data through August. There is no sign yet of a rebound in labor demand that many are hoping for.

A prolonged shutdown is certainly possible, but our base case is for the shutdown to end within a few weeks (possibly before the military payroll date on October 15) with little impact on economic data — or economic activity for that matter. The September payrolls report is likely already finalized, so it should be released quickly after reopening. September CPI data is already collected and should be published shortly after payrolls. CPI data collection is already being interrupted as BLS employees normally sample prices throughout the month. This will introduce some noise in the data if the shutdown drags on, but has proven manageable in prior instances. In any event, we think it more likely than not that the FOMC will have the September CPI and payrolls reports in hand by their October 28-29 meeting. The alternative data we’ve outlined here suggest that the labor report will not contain much good news when it becomes available.