By reducing the tariff rate on Chinese imports from 145% to 30%, President Trump significantly de-escalated his trade war and reduced the left-tail risk of a sudden forced decoupling from China. But remember that the 30% figure represents new tariffs. Those are applied on top of preexisting tariffs, many of which were initially implemented during President Trump’s first term and then maintained during President Biden’s term.

The Peterson Institute has a helpful tracker that estimates the statutory tariff rate on Chinese imports at 3% on January 1, 2018 (before Trump initiated his first-term trade war) and 21% on January 1, 2025. So, the 30% addition this year takes the statutory rate to 51%. The effective tariff rate (total tariff revenue divided by total imports) is much lower than the statutory rate because many products are exempted from the tariffs and import demand shifts away from products with the highest statutory tariffs.

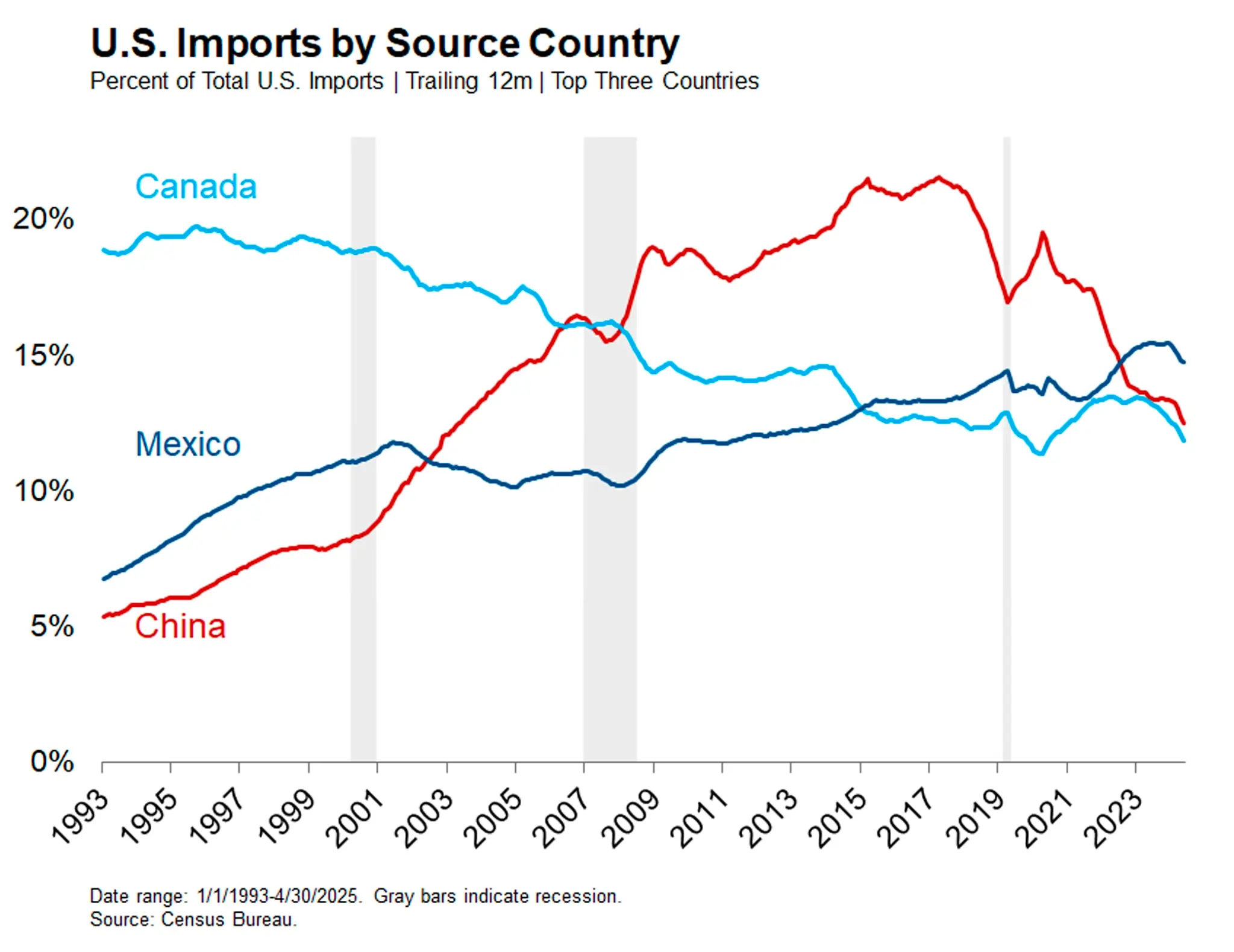

Nevertheless, both statutory and effective tariffs have increased substantially since 2018 and again in 2025. These trade barriers have had the expected (and perhaps desired) result of reducing China’s share of U.S. imports, which has been cut nearly in half since 2018 (with a large interruption during the pandemic surge in goods imports). China has also fallen out of the top rank of U.S. import sources, which they held for 15 years after the 2008 financial crisis.

A sudden forced decoupling from China would have been very disruptive to the global economy. We have avoided that outcome for now. But a more gradual decoupling remains very much underway, with all the attendant economic and geopolitical implications.