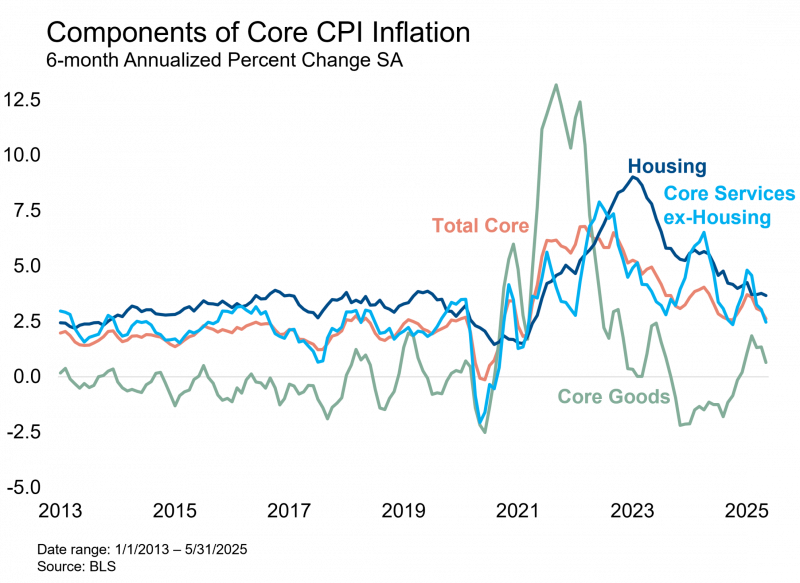

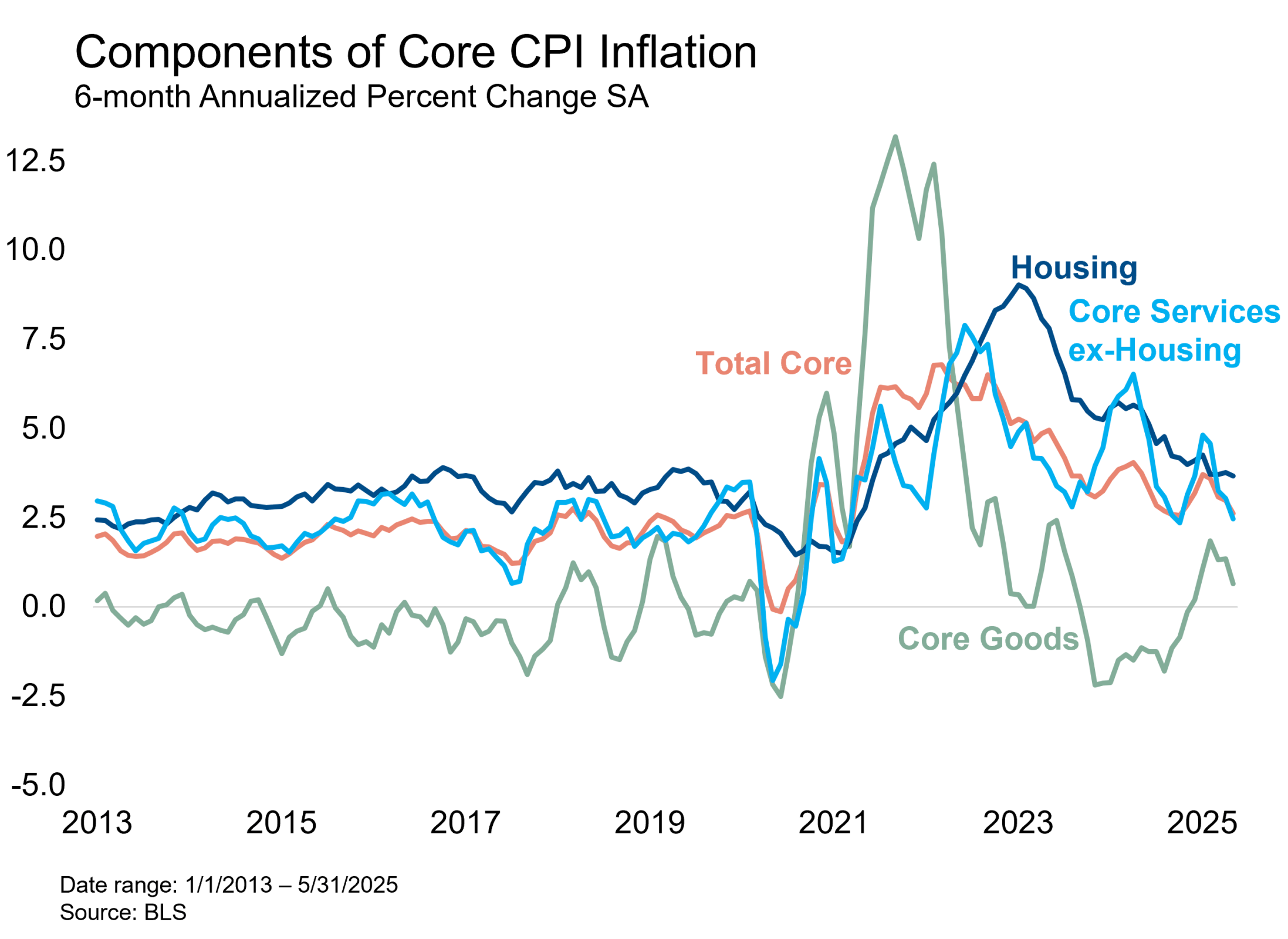

CPI inflation printed below expectations in May as isolated signs of tariff-induced inflation were offset by cooler price pressures in autos and other components. Core CPI increased by 0.13% m/m in May, which was lower than the estimates of all 73 economists surveyed by Bloomberg. Core CPI inflation has now fallen to a new cycle low of 2.74% in y/y terms. If this is indeed the final print before tariff inflation arrives, it shows that the Fed was closer than ever to achieving the soft landing. All three of the main categories of core CPI inflation decelerated in May. Core goods prices declined 0.04% in May, led by declines in new and used cars. Core services ex-housing prices rose by 0.06% in May, exhibiting continued volatility around the downtrend since 2022. Housing prices rose 0.26% in May, near the low end of recent ranges.

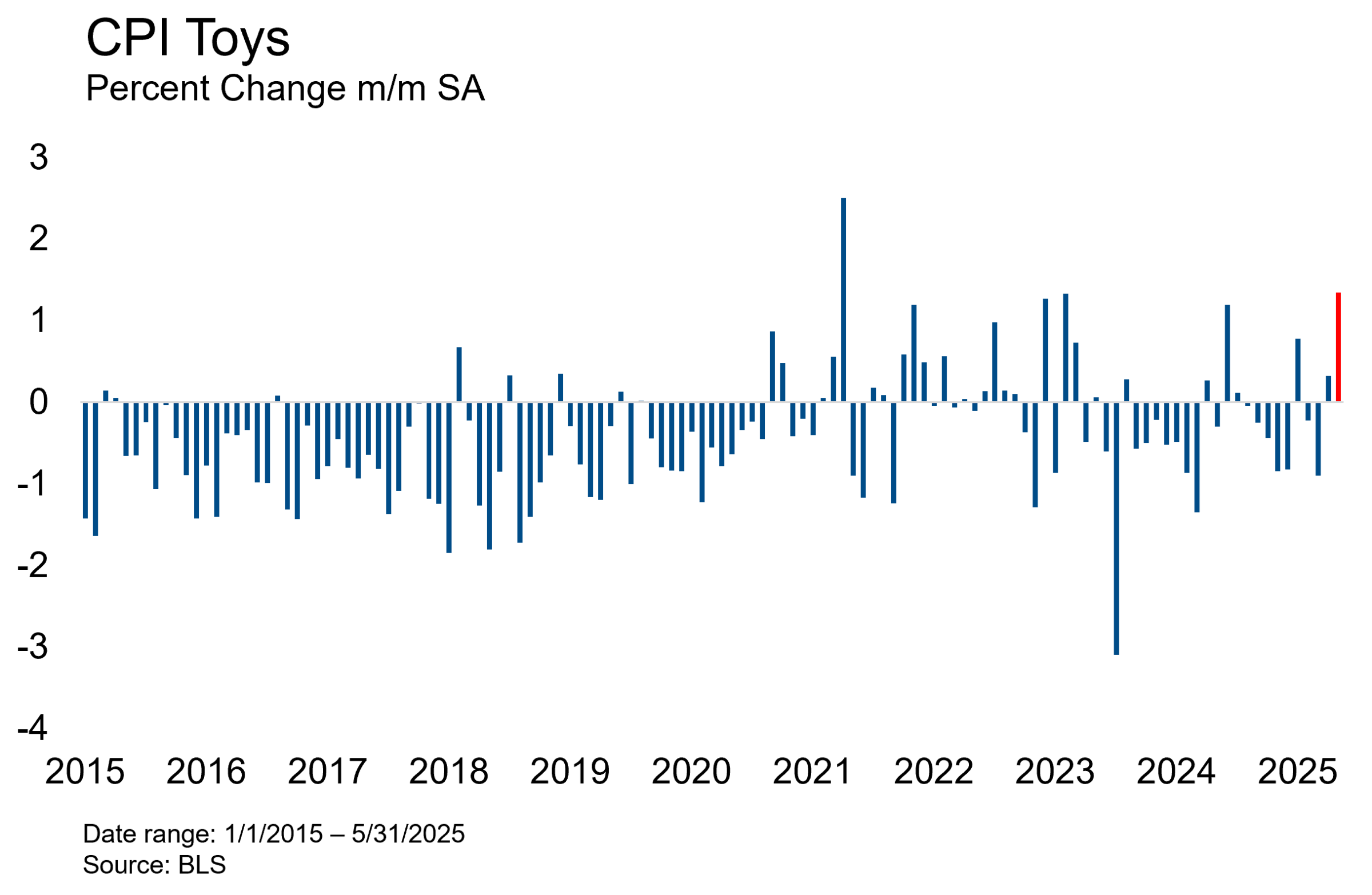

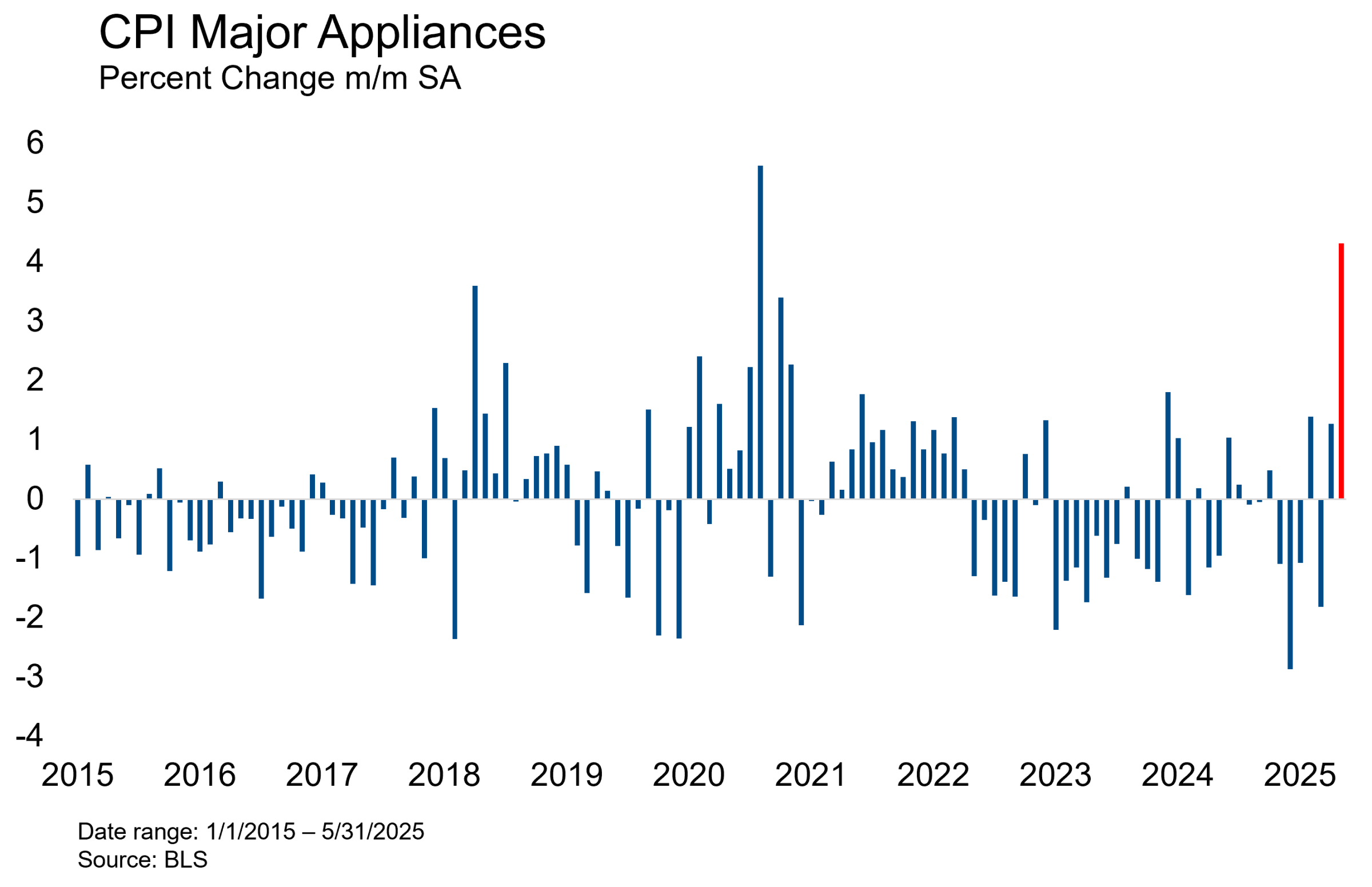

There were some isolated signs of tariff-induced inflation. Prices for toys increased at the fastest monthly pace since 2021 and the third fastest monthly pace since China joined the World Trade Organization in 2001 — likewise for appliance prices, which increased at the fastest pace since 2021 and second fastest pace on record. President Trump applied product-specific tariffs on appliances during his first term, and the inflationary impact showed up clearly in the CPI data during 2018. Auto parts prices also rose at their fastest monthly pace since 2022. These are all components where we expect to see prices increase in response to tariffs, and we can observe the price increases in the May data. That said, hot prints in these narrow components were more than fully offset by cool prints in other larger components. Toys, appliances and auto parts together represent just 0.7% of the index, compared to 6.7% for new and used cars.

Housing is the largest line item in most consumers’ budget and therefore carries a heavy weight in CPI at 35% of the total index and 44% of the core index. Housing disinflation has been frustratingly slow over the last few years. It is well understood by the Fed and market participants that the methodology underlying CPI and PCE inflation data embed long lags between observed market rents and the official housing inflation measures. Though it’s taken longer than we expected, housing inflation is now back within pre-pandemic ranges, though still slightly above the 2016-2019 average. With the housing market relatively immune from tariff effects and the labor market showing no sign of accelerating, the Fed can feel comfortable that the war against post-pandemic housing inflation has been won.

Our main takeaway from this report is that we’ll need to wait at least another month to see the inflationary impact of tariffs. This print does not change our view that the current level of tariffs will cause a 1.10-1.5% increase in the price level. We expect those price increases to be evident in the next three months of CPI data. We acknowledge the extreme uncertainty associated with that forecast, even if we could hold actual trade policy constant. This is still the largest trade policy shock in American history, so there is no precedent for how businesses will change prices and consumers will change their purchasing behavior. If tariff inflation does not appear in the next few months, the Fed would probably feel comfortable cutting rates this year. Our base case remains unchanged, that moderate stagflation will delay the first rate cut until January 2026.