Introduction

What do defined contribution participants want? When we began thinking about our glidepath framework, we started with that simple question. There is a wide and growing body of economic, demographic, and attitudinal research on this question, but it can all be distilled into two words: retirement security.

What do participants need to build and maintain retirement security? That is the question we built our glidepath framework around. And while multiple factors play a part, increasingly we think that your plan’s default and glidepath construction are the key to achieving predictable and flexible income for participants in retirement.

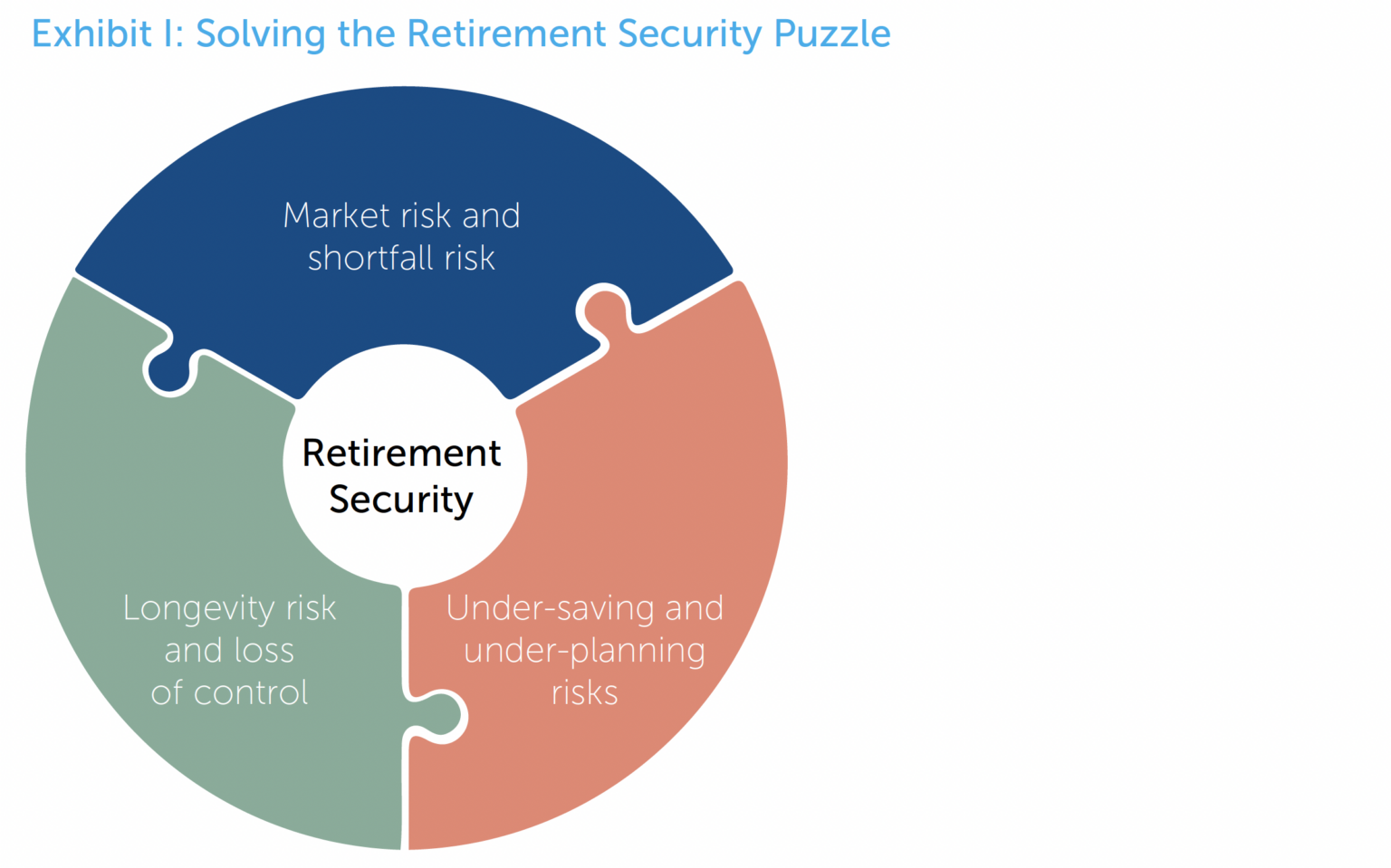

While this may seem obvious and perhaps similar to the investment objective of your existing glidepath, the difference lies principally in how the risks are defined and managed. Many traditional glidepaths shift over the lifecycle from growth-seeking to capital-preserving assets with the predominant view of risk, defined as the volatility of account balance. This emphasis on account balance may have been appropriate then, but that singular accumulation objective may no longer apply to many plans. As the average age of participants has risen and the number of participants with a defined benefit plan has decreased, it’s not a surprise that the more appropriate objective has become retirement income.

We approach glidepath design by putting the need for sustainable and stable retirement income front and center. The end result is a glidepath designed to

- align with your plan’s objectives;

- address participant’s needs to accumulate sufficient savings to retire and provide for needed spending throughout retirement; and

- be a default option aimed at overcoming behavioral hurdles that hinder participants’ ability to achieve the best retirement outcome.

In this paper, we will provide our research and methodology for how NISA can tailor a glidepath for your plan’s goals and participants’ needs for greater retirement security. In subsequent papers, we will consider the risks in retirement and ways to better meet participants’ needs for the stability of income in retirement that they can’t outlive. Additionally, we will explore the participant experience and how reframing outcomes in terms of retirement income can be simple and engaging to help participants get on and stay on track to greater financial wellness. We believe this holistic approach to glidepath, plan, and communication design can provide material improvements in retirement outcomes for participants—and move us one step closer to true retirement security.

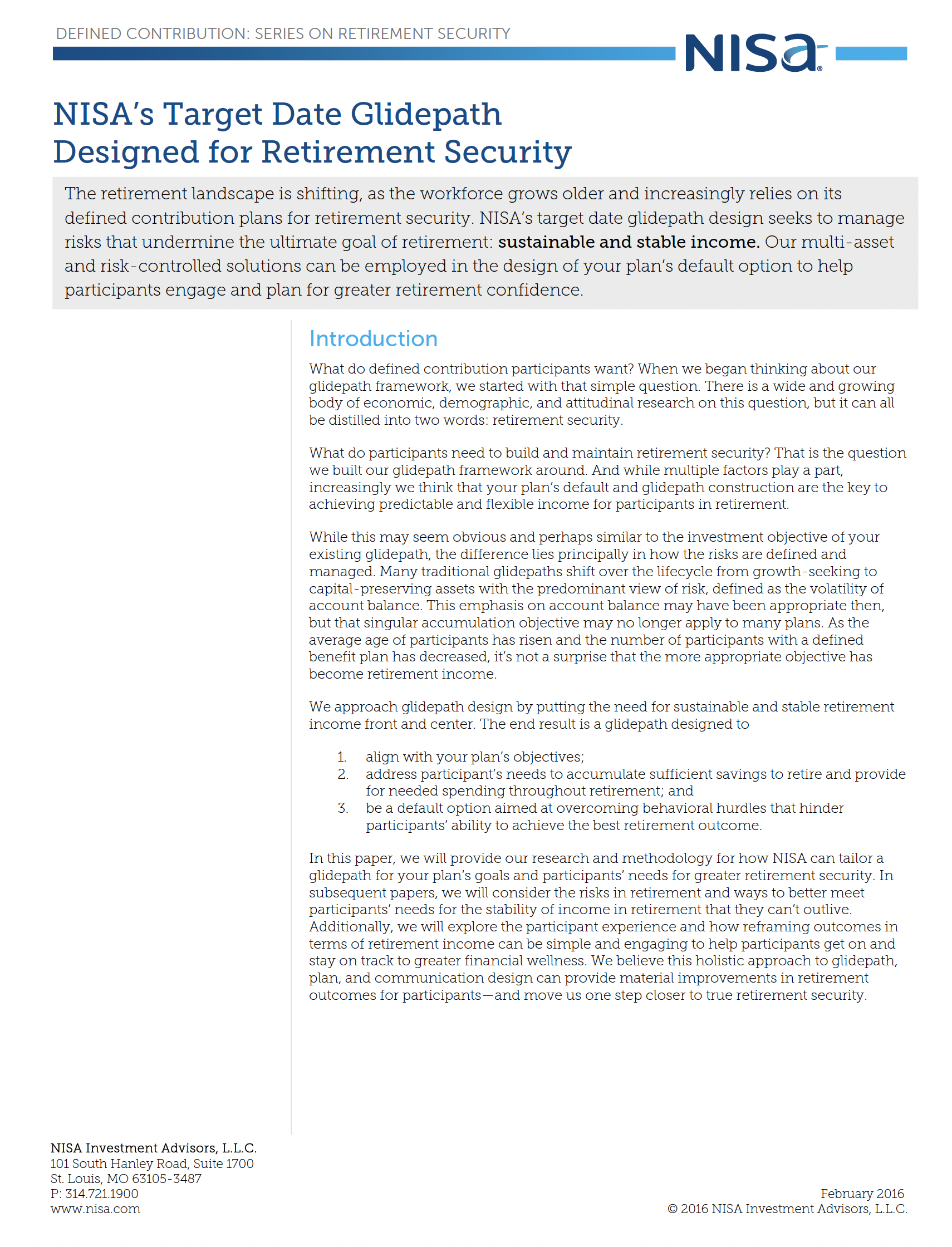

Many Risks to Retirement Security

To understand how to address the risks that participants face, we worked backwards from their desired outcome: a secure retirement.

Glidepath Construction in a Multi-Risk World

Perhaps the biggest risk to participants' retirement security comes from not managing risks.

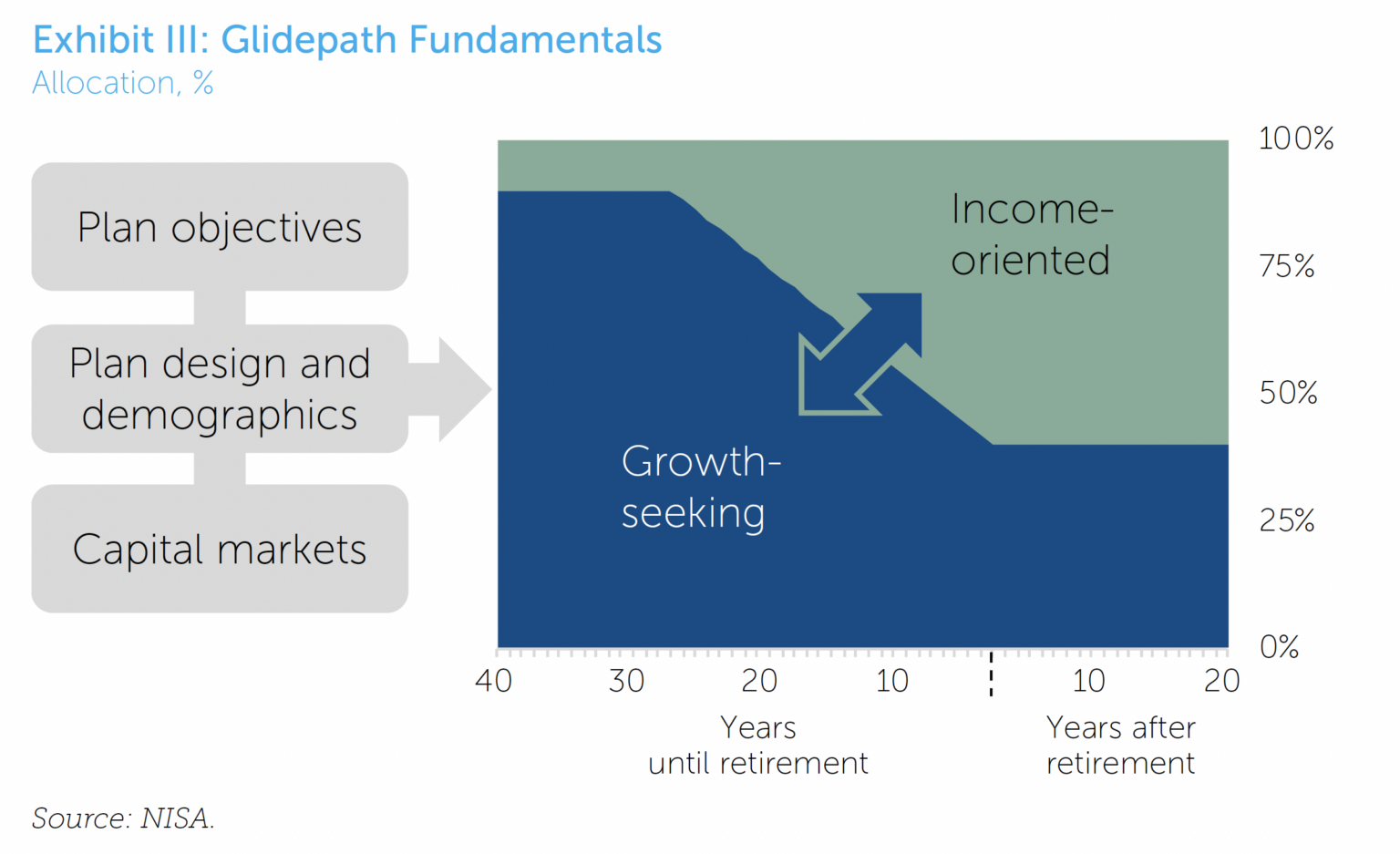

NISA's Glidepath Composition and Asset Allocation

We approach the glidepath as an allocation between assets designed to grow savings and assets designed to provide the potential stability of income in retirement.

It is often assumed that people spend in retirement like they did while working, adjusted for inflation. But retirement spending studies have shown that it is more complicated than this simple rule of thumb.

Conclusion

1. Other papers, including Long Live Longevity Annuities, The Beauty of the Bundle, and Regulators Pave the Road to Retirement Income have touched on this idea as well.

2. See the Employee Benefit Research Institute’s study, “Change in Household Spending After Retirement:

Results from a Longitudinal Sample,” for a good look at how heterogeneous retiree spending patterns

can be. Results from a Longitudinal Sample,” for a good look at how heterogeneous retiree spending patterns can be.

3. If you like, replace growth-seeking with “risky,” and income-oriented with “less risky.”

3. If you like, replace growth-seeking with “risky,” and income-oriented with “less risky.”